The Big Pang: Why You Can't Stop Eating

Photo: Thinkstock

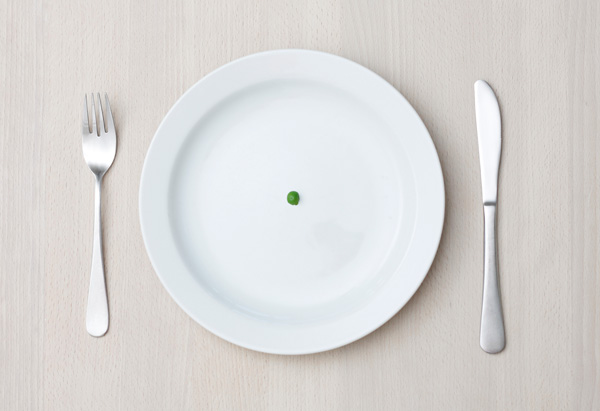

Who's in charge—you or your appetite? Eating right would be a piece of cake if it weren't for that overpowering urge called hunger. But where do those "feeeeed me!" signals really come from? Your genes? Our culture? The mysterious hunger hormones leptin and ghrelin?

Like the insatiable houseplant in Little Shop of Horrors our bodies send a message to our brains: "Feeeeed me!" The monster within us makes its relentless demand, we comply, and soon enough it rears its ugly head yet again and roars for more.

We're supposed to feel hungry when we need fuel, but hunger has become so fraught, so linked to our collectively ballooning girth, that it often seems less like a finely tuned bodily function and more like a beast in need of taming. Who's in charge—our appetites or our brains? And is there really such a thing as willpower?

The answer to the second question is yes, of course, but if we try to live by willpower alone—to eat less than nature intended us to eat, to be thinner than our genes meant for us to be—we're in for a struggle. The sad truth is that for some people, staying thin means going hungry. The much happier truth is that scientists are beginning to understand much more about how we know when, and how much, to eat. Millions of people, from the clinically obese to those struggling with an extra five pounds, stand to gain (and lose) from the researchers' insights.

A major advance in Big Pang theory came in 1995, with the discovery of leptin, the first recognized hormone that regulates body weight. "Since then, the pace of change in understanding appetite control has been exponential," says David E. Cummings, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Two years ago, Cummings himself reported that surges of another hormone, ghrelin, prompt hunger before meals. Both breakthroughs have brought us much closer to figuring out how, when, and why the creature must be fed.

In a perfect world, two to three and a half hours after eating breakfast, your empty stomach secretes ghrelin, which travels to the brain and triggers your appetite. You begin to feel physically hungry, you think about lunch, and pretty soon you're eating. The food then signals your ghrelin levels to drop off, decreasing your appetite.

As you eat, other molecules and hormones—including PYY, which was recently found to have a role in hunger—tell your brain to stop eating: Your stomach expands, and nerve impulses from the stretch receptors there, as well as hormones stimulated by food in the intestine, alert the brain that you're full. Together, ghrelin and PYY are part of a tag team of hunger, turning appetite on, then off.

Leptin also turns your appetite off, but in a longer-term way than PYY: It lets your brain know how much fat you've stored in your body. Leptin is made by the fat cells, and as fat stores rise, more leptin is secreted, traveling to the brain with the message You're fat enough—stop eating so much. If fat levels fall, so do leptin levels, and appetite increases. Mice that are genetically unable to produce leptin grow enormously obese because they never get the word to stop eating.