5 Mistakes You're Making with Chicken

There are a few tricks to avoid dried out, rubbery or charred poultry, says cooking instructor James Peterson in his new book Done.: A Cook's Guide to Knowing When Food Is Perfectly Cooked.

By Lynn Andriani

Photo: Jupiterimages/Stockbyte/Thinkstock

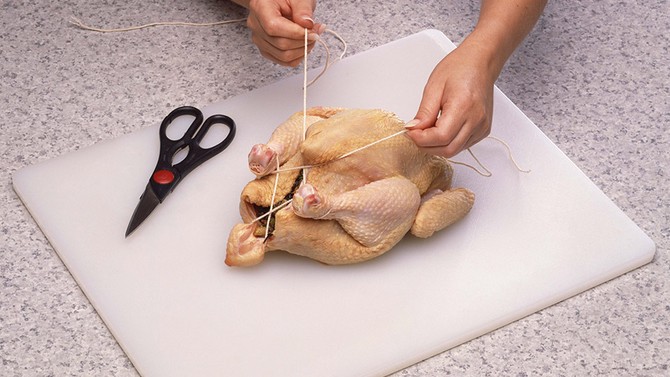

You're Letting the Legs and Wings Fly

Trussing a chicken before roasting is not just for fussy cooks who put presentation above everything else (although we'll admit, tying the legs and wings so they're tight against the body does make the finished dish look picture-perfect). The practical reason for trussing is to help the bird cook evenly and stay moist. Otherwise, hot air circulates inside the open breast cavity, drying out that portion before the legs are done. It's as simple as taking some string and securing it around the legs, as this video shows.

Photo: Olga Anourina/iStock/360/Thinkstock

You're Putting the Bird in with No Blanket

Peterson says another easy way to prevent "roasting a chicken to death" is to cover the breast with aluminum foil during the first 20 minutes of roasting. This will slow down the cooking of the breast meat so it ends up being done at the same time as the thighs. Just tent the foil (don't wrap it tightly) so air can flow underneath.

Photo: Howard Shooter/Thinkstock

You're Sautéing Just 2 Pieces of Chicken

Cooking chicken in butter on the stove yields delicious meat that's golden brown and deeply flavored. And while chefs often tell cooks "don't crowd the pan," sautéing chicken is one instance where you really can pack it in. Peterson says your sauté pan should be completely full of chicken; because, if not, the butter will burn over any uncovered patches. The chicken parts need not be touching (small spaces are fine), but don't sauté one or two pieces in a large skillet or everything will taste burnt.

Photo: Creatas/360/Thinkstock

You're Guessing When It's Done

We know an instant-read thermometer is the best way to determine doneness on a whole chicken (it should be 140 degrees where the thighbone joins the rest of the bird, says Peterson). But if you don't have a thermometer handy, use the hand test. Press on the muscle with the base of your thumb; that's what raw or undercooked meat feels like. Now make a fist and press on the muscle again; that's what cooked meat feels like.

Photo: Design Pics/Tomas del Amo/Thinkstock

You're Starting a Fire When You Grill

Flare-ups are common while grilling chicken, and are usually caused by the fat from the chicken dripping onto the coals during cooking. Although they typically aren't dangerous, they can give the meat a bitter taste (not to mention a light coating of soot). Peterson's advice is to ignore what you read in most cookbooks and cook the chicken flesh-side down first, while the fire is hottest. By the time you're ready to flip it over to the skin side, the fire will have died down somewhat and be less likely to flare up while you're grilling the skin (i.e., fatty) side.

Published 06/16/2014