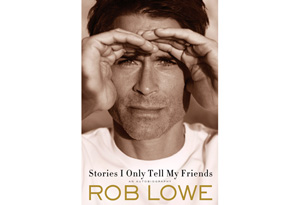

Excerpt from Stories I Only Tell My Friends

Chapter 1

I had always had an affinity for him, an admiration for his easy grace, his natural charisma, despite the fact that for the better part of a decade my then girlfriend kept a picture of him running shirtless through Central Park on her refrigerator door. Maybe my lack of jealousy toward this particular pinup was tamped down by empathy for his loss of his father and an appreciation for how complicated it is to be the subject of curiosity and objectification from a very young age. That said, when my girlfriend and others would constantly swoon over him, when I would see him continually splashed across the newspapers, resplendent like an American prince, I wasn't above the occasional male thought of: Screw that guy. As a person navigating the waters of public scrutiny, you are often unable to hold on to personal heroes or villains. Inevitably you will meet your hero, and he may turn out to be less than impressive, while your villain turns out to be the coolest cat you've ever met. You never can tell, so you eventually learn to live without a rooting interest in the parade of stars, musicians, sports champions and politicians. And you lose the ability to participate in the real American pastime: beating up on people you don't like and glorifying people you do.

I had not yet learned that truism when he and I first met. I was at a point where I was deeply unhappy with my personal life, increasingly frustrated about where my career seemed to be going–although from the outside it would probably appear to anyone observing that I was among the most blessed 24-year-olds on the planet. In an effort to find substance, meaning and excitement, I had become deeply involved in the world of politics.

It was at one of these political events, the kind where movie stars mix with political stars, each trading in the other's reflective glory, both looking to have the other fill something missing inside them, that we were introduced. "Rob Lowe, I'd like you to meet John Kennedy Jr.," someone said. "Hey, man, good to meet you," I said. He smiled. We shook hands, and I was relieved that my by then ex-girlfriend wasn't there to notice that he was slightly taller than I was, or to comment on who had better-looking hair. We made some small talk, and I remember thinking, "How does he do it? How does he carry the scrutiny? How does he attempt a normal life? Is it even possible? Is it even worth trying?"

He was charming and gracious and didn't seem to be unnerved by the multitudes of eyeballs stealing glances as we spoke. Eventually, as we were both single guys in our 20s, the talk turned to girls. "Maybe we should get outta here, go find where the action is," he said. I looked at him. "Dude. You're f******* JFK Jr.! All right?! You don't need to go anywhere!" He looked at me and laughed, and as he did I saw a glimpse of his father and was reminded of his family's legacy of sacrifice and tragedy, and was glad that he was carrying the mantle so well and with so much promise for the future.

Eventually we went our separate ways, never teaming up to hunt down any fun that night (although I later wrestled open a wet bar at 2 a.m. with a vice presidential short-list candidate). Over the years I watched him navigate the currents of fame, dating and career ups and downs, curious to see how his life would play out. Sometimes he and I would both appear on those shameful lists of "hunks." (Could there be a more degrading or, frankly, gross word than "hunk"? Hunk of what? Hunk of wood? Hunk of cheese? Yikes!) There may have even been a girl or two whom we both coveted, but that was the extent of my contact with him.

He was charming and gracious and didn't seem to be unnerved by the multitudes of eyeballs stealing glances as we spoke. Eventually, as we were both single guys in our 20s, the talk turned to girls. "Maybe we should get outta here, go find where the action is," he said. I looked at him. "Dude. You're f******* JFK Jr.! All right?! You don't need to go anywhere!" He looked at me and laughed, and as he did I saw a glimpse of his father and was reminded of his family's legacy of sacrifice and tragedy, and was glad that he was carrying the mantle so well and with so much promise for the future.

Eventually we went our separate ways, never teaming up to hunt down any fun that night (although I later wrestled open a wet bar at 2 a.m. with a vice presidential short-list candidate). Over the years I watched him navigate the currents of fame, dating and career ups and downs, curious to see how his life would play out. Sometimes he and I would both appear on those shameful lists of "hunks." (Could there be a more degrading or, frankly, gross word than "hunk"? Hunk of what? Hunk of wood? Hunk of cheese? Yikes!) There may have even been a girl or two whom we both coveted, but that was the extent of my contact with him.

In the late '90s my wife, Sheryl, and I were on a romantic ski vacation in Sun Valley, Idaho. We still felt like newlyweds, in spite of having two beautiful baby boys from whom we'd escaped for a rare evening out. Sun Valley is one of my favorite spots. It's old school (as the site of North America's first chair lift) and glamorous (the home of Hemingway and early Hollywood royalty), and boasts one of the greatest ski mountains in the country. I had been going there since the mid-'80s and always liked the mix of people you might encounter at any given time. One evening at a big holiday party, I felt a tap on the shoulder. It was John Jr. "How've you been, man?" he asked with a smile. I introduced him to Sheryl. He congratulated us on our marriage. After a while Sheryl went off on her own, leaving the two of us alone in the corner watching the party move on around us. Even in this more rarefied crowd, you could feel the occasional glare of curious observation. A ski instructor passed by, a movie star; a local ski bunny brushed by John and flipped her hair. "How did you do it?" he asked, so low against the buzz of the party that I couldn't quite hear.

"I'm sorry?"

"How did you do it?" he repeated. "I mean how did you settle down? You of all people."

I looked at him and he was smiling, almost laughing, as if covering something else, some other emotion, something I couldn't quite discern. At first I thought he might be gently poking fun at me; up until my marriage, my life had been publicly marked by a fair number of romances, some covered with great interest in the papers. But I saw that his question was real, and that he seemed to be grappling with a sort of puzzle he could not solve. I realized he was looking across the room to a willowy blonde. She had fantastic blue eyes, and the kind of beauty and magnetism that was usually reserved for film stars. She was standing next to my wife, Sheryl, also a blue-eyed blonde with a beauty and presence that made her seem as if a spotlight and wind machine were constantly trained on her.

I put two and two together. "Looks like you have a great girl. That's half the battle right there. She's obviously amazing and if she's your best friend, marry her. You can do it. Don't let anyone tell you that you can't, that you're not ready, or not capable. Come on in, man, the water's warm. I'm here to tell you it is; if she's your friend in addition to all of the other stuff, pull the trigger, don't let her get away. You never know what life will bring."

"I'm sorry?"

"How did you do it?" he repeated. "I mean how did you settle down? You of all people."

I looked at him and he was smiling, almost laughing, as if covering something else, some other emotion, something I couldn't quite discern. At first I thought he might be gently poking fun at me; up until my marriage, my life had been publicly marked by a fair number of romances, some covered with great interest in the papers. But I saw that his question was real, and that he seemed to be grappling with a sort of puzzle he could not solve. I realized he was looking across the room to a willowy blonde. She had fantastic blue eyes, and the kind of beauty and magnetism that was usually reserved for film stars. She was standing next to my wife, Sheryl, also a blue-eyed blonde with a beauty and presence that made her seem as if a spotlight and wind machine were constantly trained on her.

I put two and two together. "Looks like you have a great girl. That's half the battle right there. She's obviously amazing and if she's your best friend, marry her. You can do it. Don't let anyone tell you that you can't, that you're not ready, or not capable. Come on in, man, the water's warm. I'm here to tell you it is; if she's your friend in addition to all of the other stuff, pull the trigger, don't let her get away. You never know what life will bring."

I think he was a little taken aback at the passion of my response. I'm not at all sure what he had expected me to say. But he asked, so what the hell. John nodded and we went on to other topics. The next day, we met to ski on the mountain he snowboarded, ripping down the face, fast and free. But the weather was turning and a whiteout was upon us. In the snow and the speed and the wind, we were separated. I looked up over a ridge and he was gone, lost in the clouds.

John did marry his blonde, his Carolyn. I was glad for him and thought about sending him a note, but somehow I didn't (of all my character flaws—and there are a number of them—procrastination is one of the most distinctive). Instead I wished him luck, children and longevity of love with one of my nonalcoholic beers as I watched the coverage on Entertainment Tonight. As a political junkie and unashamed admirer of our country, I was a huge fan of his brainchild, George magazine. When someone finally stopped asking celebrities appearing on its cover to pose in those George Washington wigs I thought, "Okay, they're rollin' now!"

The end of the century approached. The '90s were a time of building for me. Building a life that was sober, drained of harmful, wasteful excess and manufacturing in its place a family of my own. This was my priority through the decade, and that work continues to pay off today with the love of my sons, Matthew and Johnowen, and the constant gift of the love of my wife, Sheryl. Whereas the '80s had been about building a career, the '90s ended with my having built a life.

At the end of the decade, my career was very much in flux, just as it had been at the end of the previous one. I had had some successes in the '90s, always made money, but the truth was I was like a man pushing a boulder up a hill. A huge, heavy, difficult boulder made up of some career mistakes, projects that didn't meet expectations, and 20 years of being a known quantity. And not only not being the new sensation, but worse, being someone people in Hollywood took for granted, someone with no surprises left in him. For example, the ability to appear on the cover of magazines is critical for any major actor. It's just a fact of the business end of show business. And I hadn't been on the cover of a magazine in almost 10 years. To have the kind of career one aspires to, comprising good, major work over the course of a lifetime, it was critical that I find two things: the breakout, watershed project to remind people what I could accomplish as an actor, and that first magazine cover and profile to publicize it. It was June of 1999 and John Kennedy Jr. was about to help me get both.

John did marry his blonde, his Carolyn. I was glad for him and thought about sending him a note, but somehow I didn't (of all my character flaws—and there are a number of them—procrastination is one of the most distinctive). Instead I wished him luck, children and longevity of love with one of my nonalcoholic beers as I watched the coverage on Entertainment Tonight. As a political junkie and unashamed admirer of our country, I was a huge fan of his brainchild, George magazine. When someone finally stopped asking celebrities appearing on its cover to pose in those George Washington wigs I thought, "Okay, they're rollin' now!"

The end of the century approached. The '90s were a time of building for me. Building a life that was sober, drained of harmful, wasteful excess and manufacturing in its place a family of my own. This was my priority through the decade, and that work continues to pay off today with the love of my sons, Matthew and Johnowen, and the constant gift of the love of my wife, Sheryl. Whereas the '80s had been about building a career, the '90s ended with my having built a life.

At the end of the decade, my career was very much in flux, just as it had been at the end of the previous one. I had had some successes in the '90s, always made money, but the truth was I was like a man pushing a boulder up a hill. A huge, heavy, difficult boulder made up of some career mistakes, projects that didn't meet expectations, and 20 years of being a known quantity. And not only not being the new sensation, but worse, being someone people in Hollywood took for granted, someone with no surprises left in him. For example, the ability to appear on the cover of magazines is critical for any major actor. It's just a fact of the business end of show business. And I hadn't been on the cover of a magazine in almost 10 years. To have the kind of career one aspires to, comprising good, major work over the course of a lifetime, it was critical that I find two things: the breakout, watershed project to remind people what I could accomplish as an actor, and that first magazine cover and profile to publicize it. It was June of 1999 and John Kennedy Jr. was about to help me get both.

My longtime publicist Alan Nierob was on the line. "Apparently JFK Jr. stood up in today's staff meeting and said he had just seen a pilot for a new TV series that was the embodiment of everything he founded George magazine to be. He was emotional about it, very moved by the show and inspired to help people hear about it. He thinks The West Wing can be one of those once-in-a-lifetime shows that can change people's lives. Your character of Sam Seaborn was his favorite, and he wants to put you on George's September cover."

Although the advance copy of The West Wing had been receiving freakishly unanimous raves, I was ecstatic and humbled by this particular endorsement. It's impossible to imagine living JFK Jr.'s life and then watching a show whose central theme was the heart and soul of the American presidency. His whole world has been shaped by the office, the service to it and the tragic sacrifice in its name. The West Wing was going to be about "the best and the brightest." His father's administration all but coined the phrase.

"Um, Alan, does John realize that there is no guarantee that the show will last through the fall?" I knew that George was in serious financial trouble and could ill-afford to feature a show with the high likelihood of attaining the ultimate creative Pyrrhic victory: worshiped by critics, ignored by the public. If the show was quickly canceled (and quite a few thought it would be) it would be a financial disaster for John and, possibly, could be the end of the magazine. "Rob," Alan said, "John is putting you on the cover. He couldn't care less."

The politics of the workplace can be complicated, Machiavellian, self-serving and just downright stupid no matter where you work. My grandpa ran a restaurant in Ohio for 50 years. I'm sure every now and then he would get nervous when his most popular carhop got uppity and started wanting better hours. My father practices law to this day and deals with those who smile to his face, then wish he would step on a limpet mine in the middle of Ludlow Street. That's the way it is in the world. It's just worse in Hollywood.

Although the advance copy of The West Wing had been receiving freakishly unanimous raves, I was ecstatic and humbled by this particular endorsement. It's impossible to imagine living JFK Jr.'s life and then watching a show whose central theme was the heart and soul of the American presidency. His whole world has been shaped by the office, the service to it and the tragic sacrifice in its name. The West Wing was going to be about "the best and the brightest." His father's administration all but coined the phrase.

"Um, Alan, does John realize that there is no guarantee that the show will last through the fall?" I knew that George was in serious financial trouble and could ill-afford to feature a show with the high likelihood of attaining the ultimate creative Pyrrhic victory: worshiped by critics, ignored by the public. If the show was quickly canceled (and quite a few thought it would be) it would be a financial disaster for John and, possibly, could be the end of the magazine. "Rob," Alan said, "John is putting you on the cover. He couldn't care less."

The politics of the workplace can be complicated, Machiavellian, self-serving and just downright stupid no matter where you work. My grandpa ran a restaurant in Ohio for 50 years. I'm sure every now and then he would get nervous when his most popular carhop got uppity and started wanting better hours. My father practices law to this day and deals with those who smile to his face, then wish he would step on a limpet mine in the middle of Ludlow Street. That's the way it is in the world. It's just worse in Hollywood.

Someone, somewhere, got it into their heads that it would be a bad thing for the launch of our new show if I was on the cover of George. It was made very clear to me that I had no right to be on this cover and that John should rescind the offer. When pushed for a reason as to why it would be a bad thing for a show no one had ever heard of to get this kind of recognition, the response was: "Everyone should be on the cover. Not you." I understood that there was no single "star" of the show, but still thought it was a great opportunity for all concerned. The higher-ups remained adamant, and they asked John to take me off the cover. He refused.

As I puzzled over (and was hurt by) this disconnect between me and my new bosses on The West Wing, John was in New York planning the cover shoot. He chose Platon, one of the great photographers, and lined up the journalist for the profile. After it was clear that John made his own choices on his covers, and could not be pushed around, the folks at The West Wing backed down and allowed an on-set visit and an additional article about the show, cast and writers to be written. John wanted to throw a party for me in New York to coincide with the magazine's release and the premiere of the show. I made plans to attend and to thank him for supporting me at a time when no one else had. I picked up the phone and called his offices, and got an assistant. "He just came out of the last meeting on your cover issue and is running late for the airport. Can he call you Monday?"

"No problem," I said, "we'll talk then."

I hung up and started preparing for Monday's table reading of the first episode of The West Wing. John hopped into his car. He was rushing to meet Carolyn and her sister Lauren, eager to get to the airport to fly them to his cousin Rory's wedding. It was a hazy summer evening, the kind we remember from childhood. He was probably excited. He was going back to his family. He was going home.

As I puzzled over (and was hurt by) this disconnect between me and my new bosses on The West Wing, John was in New York planning the cover shoot. He chose Platon, one of the great photographers, and lined up the journalist for the profile. After it was clear that John made his own choices on his covers, and could not be pushed around, the folks at The West Wing backed down and allowed an on-set visit and an additional article about the show, cast and writers to be written. John wanted to throw a party for me in New York to coincide with the magazine's release and the premiere of the show. I made plans to attend and to thank him for supporting me at a time when no one else had. I picked up the phone and called his offices, and got an assistant. "He just came out of the last meeting on your cover issue and is running late for the airport. Can he call you Monday?"

"No problem," I said, "we'll talk then."

I hung up and started preparing for Monday's table reading of the first episode of The West Wing. John hopped into his car. He was rushing to meet Carolyn and her sister Lauren, eager to get to the airport to fly them to his cousin Rory's wedding. It was a hazy summer evening, the kind we remember from childhood. He was probably excited. He was going back to his family. He was going home.

It's been my experience that when a phone call wakes you, it's never good news. I had taken a small cottage in Burbank, a few blocks from the studio for late nights and I was asleep when I got the call. It was Sheryl and I could tell she was upset. She wanted me to turn on the news.

At first it seemed like it couldn't possibly be happening. Clearly these reporters had it wrong. John, his beloved wife, and her sister would surely be found in an embarrassing mix-up or miscommunication. They could not be gone. No one is that cruel. No God can ask that of a family. No one would so much as imagine the possibility of the horrific and arbitrary sudden nature of fate. Search teams scrambled and, like most Americans, I said a prayer of hope.

Monday came. The search for John, Carolyn, and Lauren continued. At the studio the cast and producers gathered for the very first table reading of The West Wing. I stood and told the group how much John admired the show and asked that we pray for him and work with his inspiration. It was very quiet. People were numb.

Later there was talk of canceling the cover shoot, now just days away. I was devastated and in no mood for it. But John's editors insisted, pointing out that John's last editorial decision was to make this happen. It was what he wanted. By Tuesday the worst had been confirmed. The plane had been found. There were no survivors. John, Carolyn, and Lauren were gone. I heard the news on my way to the photo session.

Being on the Oval Office set is very moving. It is an exact replica of the Clinton version, down to the artwork on the walls and the fabrics on the couches. (It was designed by the amazing movie production designer Jon Hutman, who does all of Robert Redford's movies and whom I've known since he was Jodie Foster's roommate at Yale.) It is so realistic that when I later found myself in the actual Oval Office, I felt as if it was just "another day at the office." I was, however, fascinated with the one thing the real Oval Office has that ours did not, and that was a ceiling. I stood looking up at it, staring like an idiot while everyone else oohed and aahed at all the amazing historical pieces that fill the room. However, it's not authenticity that takes your breath away when you step onto that soundstage at Warner Bros. Studios. It is the solemnity of history, of destiny, and of fate; you are certain that you are actually in the room where power, patriotism, faith, the ability to change the world, and the specter of both success and tragedy flow like tangible, unbridled currents. You feel the presence of the men who navigated them as they created our collective American history, and you fully realize that they were not disembodied images on the nightly news or unknowable titans or partisan figureheads to be applauded or ridiculed. It feels as if you are standing where they stood, you can open their desk drawers, sit in their seat, and dial their phone. They are somehow more real to you now, they are not the sum of their successes or failures, they are human beings.

At first it seemed like it couldn't possibly be happening. Clearly these reporters had it wrong. John, his beloved wife, and her sister would surely be found in an embarrassing mix-up or miscommunication. They could not be gone. No one is that cruel. No God can ask that of a family. No one would so much as imagine the possibility of the horrific and arbitrary sudden nature of fate. Search teams scrambled and, like most Americans, I said a prayer of hope.

Monday came. The search for John, Carolyn, and Lauren continued. At the studio the cast and producers gathered for the very first table reading of The West Wing. I stood and told the group how much John admired the show and asked that we pray for him and work with his inspiration. It was very quiet. People were numb.

Later there was talk of canceling the cover shoot, now just days away. I was devastated and in no mood for it. But John's editors insisted, pointing out that John's last editorial decision was to make this happen. It was what he wanted. By Tuesday the worst had been confirmed. The plane had been found. There were no survivors. John, Carolyn, and Lauren were gone. I heard the news on my way to the photo session.

Being on the Oval Office set is very moving. It is an exact replica of the Clinton version, down to the artwork on the walls and the fabrics on the couches. (It was designed by the amazing movie production designer Jon Hutman, who does all of Robert Redford's movies and whom I've known since he was Jodie Foster's roommate at Yale.) It is so realistic that when I later found myself in the actual Oval Office, I felt as if it was just "another day at the office." I was, however, fascinated with the one thing the real Oval Office has that ours did not, and that was a ceiling. I stood looking up at it, staring like an idiot while everyone else oohed and aahed at all the amazing historical pieces that fill the room. However, it's not authenticity that takes your breath away when you step onto that soundstage at Warner Bros. Studios. It is the solemnity of history, of destiny, and of fate; you are certain that you are actually in the room where power, patriotism, faith, the ability to change the world, and the specter of both success and tragedy flow like tangible, unbridled currents. You feel the presence of the men who navigated them as they created our collective American history, and you fully realize that they were not disembodied images on the nightly news or unknowable titans or partisan figureheads to be applauded or ridiculed. It feels as if you are standing where they stood, you can open their desk drawers, sit in their seat, and dial their phone. They are somehow more real to you now, they are not the sum of their successes or failures, they are human beings.

Presidents get to redesign the Oval Office to their own tastes, and they have the National Gallery, Smithsonian and National Archives warehouses of priceless pieces to choose from. John Jr.'s mother knew her way around a swatch or two, so she made sure her husband's Oval Office was simple and chic (but with enough plausible deniability if called out for it) and with the proper nod to history. For the president's desk she chose the "Resolute" desk, fashioned from the timbers of the HMS Resolute, found abandoned by an American vessel and returned to England, where Queen Victoria later had the timbers made into a desk and sent to President Rutherford Hayes as a goodwill gesture. FDR also loved the desk, but insisted that a modesty panel be installed to swing closed at the front in order to prevent people from seeing his leg braces as he sat. Years later, as JFK attended to the nation's business, tiny John Jr. would be famously photographed impishly peeking out from beneath the desk's panel.

I am leaning against a replica of that desk now, the flash of the photographer's strobe jolting me, illuminating the darkened soundstage, cutting the tension and sadness of the George cover shoot. A number of staff have flown in from New York. John was more than a boss to them, obviously, and they are devastated. They share stories of John's life. Some cry, but all soldier on through this melancholy and bizarre photo shoot on the Oval Office set.

Platon wants me to embody strength, dignity and power. He is asking me to focus in on his lens, to bring the sparkle that sells magazines. But my thoughts are elsewhere. I'm thinking of how unexpected yet oddly preordained life can be. Events are upon you in an instant, unforeseen and without warning, and oftentimes marked by disappointment and tragedy but equally often leading to a better understanding of the bittersweet truth of life. A father is taken from his son, a promise is unfulfilled and then the son is reunited with him, also in an instant and under the cover of sadness. A theme continues in that unique, awful beauty that marks our human experience.

The flash explodes in my face again. I put on a smile (none of these shots will ever be used) and remind myself that John's journey is over, and, with some thanks to him, a new journey for me is ahead. I never knew him well. Many Americans also felt a connection to him without knowing him at all. In some ways, he was America's son. But I will always be moved by John Kennedy Jr.'s steadiness in the harsh, unrelenting spotlight, his quest for personal identity and substance, for going his own way and building a life of his choosing. I will always remember his support and kindness to me and be grateful to him for being among the first to recognize that with my next project, The West Wing, I just might be a part of something great.

I am leaning against a replica of that desk now, the flash of the photographer's strobe jolting me, illuminating the darkened soundstage, cutting the tension and sadness of the George cover shoot. A number of staff have flown in from New York. John was more than a boss to them, obviously, and they are devastated. They share stories of John's life. Some cry, but all soldier on through this melancholy and bizarre photo shoot on the Oval Office set.

Platon wants me to embody strength, dignity and power. He is asking me to focus in on his lens, to bring the sparkle that sells magazines. But my thoughts are elsewhere. I'm thinking of how unexpected yet oddly preordained life can be. Events are upon you in an instant, unforeseen and without warning, and oftentimes marked by disappointment and tragedy but equally often leading to a better understanding of the bittersweet truth of life. A father is taken from his son, a promise is unfulfilled and then the son is reunited with him, also in an instant and under the cover of sadness. A theme continues in that unique, awful beauty that marks our human experience.

The flash explodes in my face again. I put on a smile (none of these shots will ever be used) and remind myself that John's journey is over, and, with some thanks to him, a new journey for me is ahead. I never knew him well. Many Americans also felt a connection to him without knowing him at all. In some ways, he was America's son. But I will always be moved by John Kennedy Jr.'s steadiness in the harsh, unrelenting spotlight, his quest for personal identity and substance, for going his own way and building a life of his choosing. I will always remember his support and kindness to me and be grateful to him for being among the first to recognize that with my next project, The West Wing, I just might be a part of something great.

Excerpted from Stories I Only Tell My Friends by Rob Lowe. ©2011 by Rob Lowe. Published in 2011 by Henry Holt and Company. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.