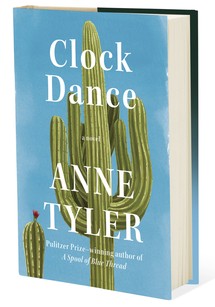

Clock Dance

By Anne Tyler

304 pages;

Knopf

For half a century, Anne Tyler has been writing exquisite novels whose characters, all ordinary people, rarely venture far from home yet feel as exotic as time travelers. Her latest, Clock Dance (Knopf), is primarily the story of Willa: her childhood, her marriages, and, most poignantly, how she grapples with the emptiness of a life not quite lived in full. O books editor Leigh Haber sat down with the author of 21 novels, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Breathing Lessons, to learn more about how she spins the dross into gold.

LEIGH HABER: The page is blank, and you're starting a new book. How do you begin?

ANNE TYLER: I think, "Well, I feel like writing about a man this time." Or, "I'm sick of first person. Let me try a different point of view." It could be that I overhear a couple arguing and am intrigued. It's like moving puppets around.

LH: And something kicks in?

AT: Yes. Early on, it's very engineered. Then I just allow the book to happen.

LH: You still write longhand, right?

AT: When I use a pen, it's as if something flows through my fingers to the paper. They're my words. When I finally type it into the computer and print it out, I glide too easily over mistakes—or lies, which is how I think of them. Writing longhand, I can feel, "Oh, I didn't tell the truth there. I wasn't being authentic."

LH: Do you ever get stuck?

AT: Of course, and when I do, I look to a quote that hangs over my desk by the poet Richard Wilbur: "Step off assuredly into the blank of your mind. / Something will come to you."

LH: In Clock Dance, we first meet Willa as a little girl. The novel next jumps to her college years, then to Willa in her 40s...

AT: Originally, I had a different character opening the book and was going to weave in Willa's childhood using flashbacks. But I thought, "No, that's cheating." So I started with Willa. But I didn't want people to have to go through every moment of her life—that would be dull. So I can bypass all the stuff we really do know—and trust my readers to figure out what's in the middle.

LH: Do you prefer writing description or dialogue?

AT: I love dialogue. It's like I'm taking dictation and being constantly surprised by what my characters say. But between their spoken lines, I have to get them from one room to another—and remember that no one's had lunch yet, and they can't throw their arms around a person because they're holding a glass of iced tea.

LH: Even if it's as simple as Willa's father making her grilled cheese, you write those nuts and bolts as if you relish them.

AT: I'm bored to death writing those things, so I try to snag one tiny detail that will keep me interested and, therefore, I hope, the reader.

LH: At one point the narrator says this about Willa: "Behind her adult face a child about eleven years old was still gazing out at the world." I think that's true of many of your characters. Is it true of you?

AT: Absolutely. In fact, age 7 would be more accurate. But no one believes me when I tell them that every wise decision I've made, the sense of myself I have, came when I was 7.

LH: After Willa experiences a devastating loss, her father suggests she break the days into moments to deal with her grief.

AT: When my husband died more than 20 years ago, I remember wondering, "How will I get through the rest of my life?" I decided not to think about that, but to just have a cup of coffee. The coffee tasted good. It was a nice day. Bit by bit, the years went by. That's what I wanted for Willa.

— Leigh Haber