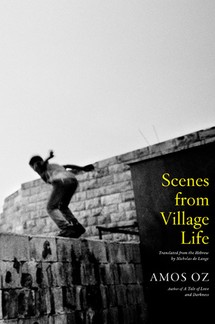

Scenes From Village Life

By Amos Oz

192 pages;

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

In fiction, there are usually two kinds of mysteries. The first is when we, the readers, don't understand what is happening because it defies the logical course of reality (example: a woman flies over the town) but eventually we get some kind of a explanation by the author (oh! she's an angel). The second is when we don't understand what is happening (example: a woman is flying over town) and we don't get an explanation, which can be very frustrating, enough so to put the book down—except in the case of a master storyteller such as Amos Oz who knows how to leave the mystery in the mysterious, while still breaking your heart.

Take his first story, Heirs, in which a greasy, wheedling cousin shows up at a man's door and tries to get him to sell his elderly mother's house. We're never sure if this cousin is real or just some kind of psychological ghost who represents all the less-than-admirable daydreams of the son. The same goes for a digging sound that a schoolteacher hears under her house at night: Is she going crazy? Or is she being haunted by the past? Either explanation works—due mostly to dreamlike prose which slides you right into these seven tales as if you'd spend your whole life in a country village in Israel, dotted with fig trees, dusty sunlight and roaming cats.

The same characters turn up again and again—each dressed in the kind of details that make you remember them as flawed but lovable friends, like Danny Franco "who looked like wardrobe set on stick legs" or Adel the young Arab student who "walked around the yard wearing a Van Gogh straw hat and an expression of wonderment." One of the most moving is Gili Steiner, the town doctor, who wanders through one foggy night, searching for her nephew who was supposed to arrive on a bus from the city but who did not, or who was perhaps never supposed to arrive—yet another case of the unexplained. The point, luckily, is not what actually happened to her nephew. The point is: The nephew is not there. And Gili Steiner's disposal of the baked fish dinner which she had cooked for him, her few rough minutes sitting at the kitchen table with his childhood stuffed kangaroo, crying until the moment she abruptly "stopped, took the laundry out the dryer, and...ironed and folded everything and put it way," is one of the most realistic portraits of the mystery of love and loneliness ever written.

— Leigh Newman