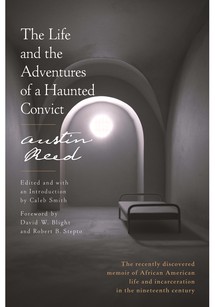

The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict

By Austin Reed

352 pages;

Random House

Austin Reed's The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict was written by hand on sheaves of paper, started, perhaps, in the 1840s and completed in 1858. It then spent 150 years unread, until rare-books dealers discovered it at an estate sale in Rochester, New York. Believing they'd stumbled across something important, in 2009 the dealers brought the manuscript to Yale, where researchers pored over it, testing the ink and paper and unearthing 19th-century prison records, deeds, and other documents. They verified that its long-dead author was who he professes to be on the page.

Reed's story is like something out of a Charles Dickens novel, complete with deprivation, unprovoked punishment, and cruel twists of fate. It takes place before the Civil War; though Reed and his family were free Northerners, his father's death propelled them into poverty and young Reed into a state of grief and anger that landed him at age 10 in a New York City juvenile facility ironically called the House of Refuge. (It was not uncommon then for children in poor families—especially poor black families—to be removed from their home for petty crimes and institutionalized in this way or made indentured servants.) We're there as the author is lashed with a crudely fashioned instrument he refers to as "the cats"; as he subsists for days on bread and water in a cell; as he repeatedly escapes, hiding out in sailing ships and saloons, only to be found, returned to the facility, and beaten yet again. Reed later ends up in an adult prison, where, aside from short periods of freedom, he remains until he's released for good in his early 40s. There are many reasons this book is remarkable, not least that while Reed is brutalized regularly, he remains triumphantly defiant. Though the only formal education he received was while in the House of Refuge, he writes with a novelist's sense of nuance and adventure—or misadventure. The memoir anticipates that the American penitentiary system would become a kind of successor to slavery's shackles. But the book's greatest value lies in the gap it fills: As writer and historian Edward Ball notes, "the mosaic that is the history of the common man has many missing tiles, and Reed's book places an important piece into that mosaic."

— Leigh Haber