For Novelist Anne Tyler, Familiarity Soothes and Haunts

If Anne Tyler were a saint, she'd be patron of the everyday. Since the publication of her first novel,

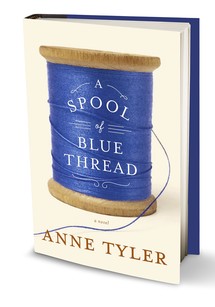

If Morning Ever Comes, more than 50 years ago, she has served up fictional worlds inhabited by modest, decent, earnest characters who struggle, make mistakes, don't take themselves too seriously and mostly live in Baltimore. In

A Spool of Blue Thread, Tyler's 20th novel, she interweaves the tales that form the history of the Whitshanks, who have lived for some seven decades in a handsome house in a quiet, leafy neighborhood. They are hardworking and good-natured, often confused by life but bent on doing their best.

Tyler tenderly unwinds the tangled skeins of three generations, then knits them together: Junior and Linnie Mae, the first Whitshanks to arrive in Baltimore; their son, Red, and his wife, Abby; Red and Abby's four children. Theirs is a classic American quest—to rise into another socioeconomic stratum. People assume Junior Whitshank—with his blue-black hair and blue-white skin, his high cheekbones and rangy build—is from Appalachia, concluding he is "trash". But he's a master carpenter and he builds a house for someone richer, then later buys it for himself and his clan. That structure with its wide porches, pocket doors and wooden ceiling fans, everything beveled and dovetailed and chamfered, is both a symbol and evidence of the family's ascent into the middle class, which Tyler renders in precise, often hilarious detail.

Storytelling is the glue that binds the Whitshanks together, with certain familial tales told and retold. For example, Abby is fond of relating how she fell in love with Red: "It was a beautiful, breezy, yellow-and-green afternoon," she always begins and everyone settles in to hear it again. But, of course, stories are unreliable and the members of one family may have conflicting versions of the same myth. By the end of this deeply beguiling novel, we come to know a reality entirely different from the one at the start. Not that anyone's lying, only that everything—the way we see the world and the way we understand it to work—is changed by the intimate, incremental shifts of daily life.