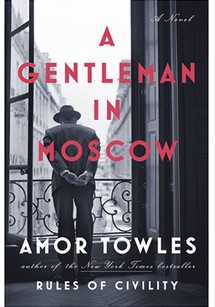

In his second elegant period piece, investment banker turned novelist Amor Towles continues to explore the question of how a person can lead an authentic life in a time when mere survival is a feat in itself.

Rules of Civility, Towles's debut, portrayed a young man who smoothed his path to Manhattan society's upper echelons with the help of etiquette guidelines laid down by George Washington. In A Gentleman in Moscow, which begins after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Towles's protagonist, Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, aspires to move

down the social ladder, transforming himself from count to comrade to save his Soviet-era skin while preserving his Russian soul.

Towles's tale, as lavishly filigreed as a Fabergé egg, gleams with nostalgia for the golden age of Tolstoy and Turgenev. The story begins in 1922, when the amiable count has been sentenced to house arrest within the precincts of Moscow's opulent Hotel Metropol. As a nobleman, or "Former Person," Rostov is regarded as a class enemy. If he so much as sets foot outside the hotel, his Bolshevik judges warn him, he will be shot. The count is only 32; for more than three decades, he will remain a captive of the Metropol.

With a dash of Dumas and a soupçon of Frances Hodgson Burnett, Rostov exchanges staterooms for a garret, adapting to his reduced circumstances with grace and, soon enough, connecting with fellow residents. He acquires a sidekick named Nina, a plucky hotel denizen who is the daughter of a well-connected apparatchik. Despite Nina's Communist mindset, she presses the count for recollections of princesses and duels from his youth. And Rostov kindles a romance with a glamorous film actress; their affair will outlast both Lenin and Stalin. Like Chekhov, Towles knows that "a story without a woman is like an engine without steam." But the abiding romance here is with Russia's literary past, which the author burnishes and carries shiningly forward, reminding the reader that though Putin may be having a moment, it's Pushkin who's eternal.