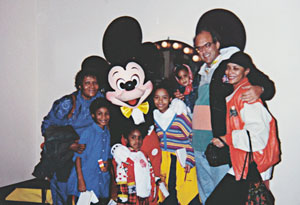

The Williams and Cooper clans at Disney World.

Shep Gordon earned crazy money guiding the careers of big acts like Alice Cooper. But his unlikely bond with four motherless kids is the thing that made him rich.

Shep Gordon never worked small. A talent manager with a vaudevillian's sense of shamelessness and show, he crafted gaudy careers for '70s and '80s legends like Alice Cooper, Teddy Pendergrass, Luther Vandross, and Raquel Welch by testing the limits of decency and doing just about anything to get attention. He recast the suit-and-tie-wearing Pendergrass as an oiled-up, rutting balladeer, while Cooper became the zany ghoul in dripping greasepaint, boa constrictor draped casually across his shoulders. Gordon helped conceive the stage spectacles that made Cooper a notorious draw—morality plays in which he savaged female effigies or chopped up baby dolls, and as "hanged" or "guillotined" for his trouble. Gordon also packaged one of the band's album in paper panties, an put a huge photo of Cooper—nude but for a snake coiled around his privates—on the side of a flatbed truck, then paid the driver to "break down" in London's West End during rush hour. He brought diabolical cunning to his stunts, although his least cunning may well have been his most regrettably effective: During a concert in Toronto in 1969, Gordon hurled a live chicken onstage, hoping to generate a headline or two. Assuming a thing with wings could fly, Cooper flung it back. When the luckless bird sank into the churning crow, it was promptly torn to shreds. Cooper's reputation as a chicken-killing freak (and hero to the pimply and disaffected) was made.

Soon Gordon was a player, traveling on the Concorde in silk suits and shades; at his height in the '80s, his management company, Alive Enterprises, was grossing upwards of $22 million a year. In his spare time he slept with models, dated Sharon Stone, and married (then quickly divorced) a Playboy Playmate he'd met at Hef's mansion. He drove a white Bentley and a white Rolls, and rattled around a succession of absurdly large homes; his Brentwood spread had so many rooms, there were six he never even entered.

He was living the life, beyond anything he'd ever imagined. What more could a guy like him want? Certainly not a bunch of orphaned kids to take care of. What on Earth would Shep Gordon do with a bunch of orphaned kids?

Wealth and fame in the land of pop music didn't seem to be in the cards when Shep was a boy. He was raised in a Long Island suburb by a CPA father and a formidable mother; he always felt she preferred his older brother. "I was sort of the ugly duckling, and my brother was the perfect person," says Shep, pleasantly paunchy now, with silver fringe ringing the base of his scalp. At 66 he exudes an everyman mildness that's difficult to reconcile with the go-go deal maker he used to be.

A future veterinarian, Shep's brother loved animals—particularly his mutt, Skippy, who didn't care for Shep; as a result, "I spent most of my youth in my bedroom with the door locked so I wouldn't get bit," Shep says. "Which in some ways was very good because I had to become independent. I watched TV, I read, I daydreamed—about getting out of the house and having a life."

When that blessed day finally came, Shep chose the farthest school the New York state university system had to offer: SUNY Buffalo. Then he went to New York's New School for Social Research for a master's in sociology, supporting himself with odd jobs, the oddest of which was shipping backless garments to funeral homes for corpses to wear. In 1968 he headed to Los Angeles, lasting a single day as a probation officer before meeting up with a college friend, Joe Greenberg, at the fabled rock 'n roll mecca the Hollywood Landmark hotel. Jimi Hendrix was hanging out there, along with the Chambers Brothers and Janis Joplin (who, on Shep's first night, made her presence known by having sex, loudly, on the pool's diving board). Shep and Greenberg were told they looked like rock managers; furthermore, there was a fledgling band living the the Chambers Brothers' basement—Alice Cooper—that needed one. Desperate for a gig but clueless about what such a job might entail, the buddies from Buffalo figured they could fake it. Alice Cooper likes to say that his and Shep's long, fruitful relationship was forged on lies: In their first meeting, Shep said he was a manager; Alice said he was a singer.

Gordon on dad duty with Keira, Chase, and Winona.

By 1973 Shep was building his management company and working bicoastally (he and Greenberg would part ways the following year). In New York, Alice's road manager, Fat Frankie, set up Shep on a blind date with a chic black Wilhelmina model named Winona Williams. Both were 27 at the time, and drama was in their DNA: Leaving a club on one of their first dates, their taxi crashed into a Daily News truck; in a curiously bonding quirk of fate, the each received gashes over their eyes that required about 16 stitches apiece. Armed with pain pills, they left the hospital at 3:30 a.m. to recuperate at Shep's place downtown. A few days later, Winona said, "I have a daughter. Can I bring her over?"

She was a beautiful girl, 8 years old, named Mia; Winona's mom, Ruth, had been babysitting her at her home in Newark, New Jersey. For Shep, getting comfortable with a child was process, but he was won over by Mia's innocence. "That was my first taste of really pure love," he says, in his deceptively gruff basso. "I loved hanging out with her." Eventually, the three set up house, kicking back at Shep's mansion in Copiague, New York, on weekends, before moving in 1975 to L.A.; Shep paid the tuition for Mia's boarding school in Ojai. But with the demands of his work—to say nothing of his unease with long-term relationships—Shep and Winona broke up a few years later. He and Mia stayed in touch, Shep sending her money from time to time. When he realized she was using it for drugs, he stopped answering her letters and phone calls.

In 1991 Shep received a call from Winona: Mia had died. She was pulling into her driveway one morning when a bus hit her car, which was both tragic and ironic, given that she had recently weaned herself off drugs. "It was almost as if Satan said, 'Uh-uh—I've had you in my grasp much too long, I'm not letting you go,'" Winona says now. "And God said, 'Look, I can't interfere, but what I can do is not let it go down the way you think it's gonna go down.' And consequently, she left a legacy of having died in a car accident and not from a drug overdose."

Looking like toughs from a mob movie, Fat Frankie and Shep (silk suit, shades, dark topcoat, ponytail) showed up at the funeral in Newark, where Winona was living with her mother, working in their in-home hair salon. Winona was lovely as ever, but surrounded now by four little kids: Monique, 9; Chase, 6; Amber, 3; and a baby girl named Keira, tucked in Winona's arms. Four indescribable little faces—Mia's kids, it turned out.

Shep asked Winona what was going to happen to them. "There's a foster family that's already taking care of Keira," she said. "I don't know what we're gonna do." And some small thing inside Shep clicked.

"It seemed like something had to be done, and I had the resources," he says. "I had to make a choice: 'Do I get this out of my brain and go back to my life?' If I did, I would have to think of those four sets of eyes every time I bought a bottle of Dom Perignon."

So Shep pulled Winona aside—even after being apart for a decade, their bond was strong—and said, "I have no idea if I can give anything emotionally, but economically, I know at least for the next while, I can support all of you. So if you'll give up your life for the next 18 years and raise them, I'll pay for it."

With little hesitation, Williams signed on. The foster family caring for Keira had already pierced her ears; deeply disappointed to have to give her up, they removed the diamond studs and handed the baby over.

In the chill wind of a late October day, leaves skitter and eddy in the driveway of Winona Williams's five-bedroom Tudor home in upstate New York—the one Shep bought for her and the kids after Mia's funeral. The house is both spacious and cozy with a fire crackling in the fireplace and Williams's vibrant oil paintings—still lifes, florals, portraits of herself, her mother—lining some of the walls. Coco, a black dog with a white big, is running around out back.

At 66, Winona—fine-boned with dark eyes, wearing tight black pants, a black sweater, over-the-knee boots, and an animal-print scarf wrapped around her head—looks 20 years younger. The oldest of the kids, Monique, who works at an auto parts store nearby, is warming herself by the fire; she has the mellow, sloe-eyed beauty of Lisa Bonet from The Cosby Show. Shep bear-hugs both when they answer the door. They have an easy rapport—Shep and Winona tossing glances and weary smiles back and forth in the manner of a long-married couple.

She was a beautiful girl, 8 years old, named Mia; Winona's mom, Ruth, had been babysitting her at her home in Newark, New Jersey. For Shep, getting comfortable with a child was process, but he was won over by Mia's innocence. "That was my first taste of really pure love," he says, in his deceptively gruff basso. "I loved hanging out with her." Eventually, the three set up house, kicking back at Shep's mansion in Copiague, New York, on weekends, before moving in 1975 to L.A.; Shep paid the tuition for Mia's boarding school in Ojai. But with the demands of his work—to say nothing of his unease with long-term relationships—Shep and Winona broke up a few years later. He and Mia stayed in touch, Shep sending her money from time to time. When he realized she was using it for drugs, he stopped answering her letters and phone calls.

In 1991 Shep received a call from Winona: Mia had died. She was pulling into her driveway one morning when a bus hit her car, which was both tragic and ironic, given that she had recently weaned herself off drugs. "It was almost as if Satan said, 'Uh-uh—I've had you in my grasp much too long, I'm not letting you go,'" Winona says now. "And God said, 'Look, I can't interfere, but what I can do is not let it go down the way you think it's gonna go down.' And consequently, she left a legacy of having died in a car accident and not from a drug overdose."

Looking like toughs from a mob movie, Fat Frankie and Shep (silk suit, shades, dark topcoat, ponytail) showed up at the funeral in Newark, where Winona was living with her mother, working in their in-home hair salon. Winona was lovely as ever, but surrounded now by four little kids: Monique, 9; Chase, 6; Amber, 3; and a baby girl named Keira, tucked in Winona's arms. Four indescribable little faces—Mia's kids, it turned out.

Shep asked Winona what was going to happen to them. "There's a foster family that's already taking care of Keira," she said. "I don't know what we're gonna do." And some small thing inside Shep clicked.

"It seemed like something had to be done, and I had the resources," he says. "I had to make a choice: 'Do I get this out of my brain and go back to my life?' If I did, I would have to think of those four sets of eyes every time I bought a bottle of Dom Perignon."

So Shep pulled Winona aside—even after being apart for a decade, their bond was strong—and said, "I have no idea if I can give anything emotionally, but economically, I know at least for the next while, I can support all of you. So if you'll give up your life for the next 18 years and raise them, I'll pay for it."

With little hesitation, Williams signed on. The foster family caring for Keira had already pierced her ears; deeply disappointed to have to give her up, they removed the diamond studs and handed the baby over.

In the chill wind of a late October day, leaves skitter and eddy in the driveway of Winona Williams's five-bedroom Tudor home in upstate New York—the one Shep bought for her and the kids after Mia's funeral. The house is both spacious and cozy with a fire crackling in the fireplace and Williams's vibrant oil paintings—still lifes, florals, portraits of herself, her mother—lining some of the walls. Coco, a black dog with a white big, is running around out back.

At 66, Winona—fine-boned with dark eyes, wearing tight black pants, a black sweater, over-the-knee boots, and an animal-print scarf wrapped around her head—looks 20 years younger. The oldest of the kids, Monique, who works at an auto parts store nearby, is warming herself by the fire; she has the mellow, sloe-eyed beauty of Lisa Bonet from The Cosby Show. Shep bear-hugs both when they answer the door. They have an easy rapport—Shep and Winona tossing glances and weary smiles back and forth in the manner of a long-married couple.

The family poses with Mickey Mouse in 1995

While Winona and the kids settled in that first year, Shep spent his time in L.A. and Hawaii, where he had homes—working, of course, but also keeping a safe distance from any emotional entanglements in New York; his preference was to say it with cash. He was more of a concept—a big checkbook—to the family than any sort of flesh-and-blood presence. Each night at dinner, they said a prayer for this faceless but bountiful figure in their lives. Monique was old enough at the time to know what he—whoever he was—had spared them in Newark: the violence, the tension, the sound of gunshots. "I remember being, like, 'Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God, I don't want to be here anymore—I don't want to live here,'" she says. "It was so scary to know that other people were losing little brothers and sisters to bullets, losing parents. I was so glad I wasn't in Newark anymore."

Though Winona kept inviting Shep to come an visit, he always had an excuse. But then, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, the resistance fell away. Part of it was the kids' innocence—the same thing that had drawn him to Mia; part of it was this unexpected chance to redo his own past. "I woke up one day," Shep remembers, "and said, 'Let me get my childhood back with these guys." A door opened—he had an idea. "I called up Winona and said, 'Do you think everybody would like to go to Disney World?'" Shep says. "She said, 'Are you kidding?' I'd never been to Disney World, and I always wanted to go. And I couldn't imagine a better way than with four kids."

Before setting off for Orlando, however, Shep had to properly introduce himself. Ever the showman, he arrived at the kids' front door wearing a Rasta wig.

It could have backfired, but once the children recovered from the ridiculous sight, they all laughed and welcomed this large, silly, incredibly important man into their lives.

Says Winona, "The showing up was the commitment: 'Okay, he's here.' Thus, the journey begins. The 18-year journey."

Henceforth, the Champagne-swilling hotshot would be known as Grandpa Shep.

In the beginning, none of us thought about being married, none of us thought about having kids," says Alice Cooper, propping his feet, clad in black boots embossed with a skull and crossbones, on the coffee table in his suite at New York's Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. He's here rehearsing for the next night's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, during which he and his former band will be inducted. The familiar, stringy dyed-black ultra-shag frames his open, amused, middle-aged face; with different hair and clothes he could be selling insurance. "All we cared about was where the next show was, and is there gonna be beer there. :ater on when we got past the insanity of the rock star thing, it was suddenly, 'Okay, now we have to start controlling this lifestyle because we want to live through it.' That's when people starting getting interested in settling down." In 1975 Cooper met Sheryl Goddard, a ballet-trained dancer on his Welcome to My Nightmare tour; they've been married 35 years, surviving Cooper's battle with alcohol, among other things, and have three kids, ages 19, 26, and 30.

When the children were little, in the early '90s, they magically acquired four instant "cousins" in the form of Shep's kids. "I had Amber on one hip, my daughter on the other hip, and they were just my own," says Sheryl Cooper. The rambling clans—Winona and sometimes her mother included—vacationed together. "We spent a lot of time in Hawaii, down in Florida at Disney World, Europe," says Alice. ("Yeah, we did all that family stuff," Shep says later, with a proud, contented chuckle.) "His kids came on tour. The band had a bus and Shep got another bus—I said, 'Great, that'll be the kids' bus.'" Shep made every outing a party, colonizing tables at restaurants and ordering everything on the menu with a wave of his hand. He frequently brought other bold-faced friends into the mix—big-deal guys who seemed both inspired and abashed by what Shep had taken on: When the kids were in Hawaii, former NBA coach Don Nelson ("Uncle Donny") picked them up every day and took them to his home to swim; actor Tom Arnold had a standing game of pool with Amber and once missed a flight in order to fit it in. The only way he knew how, Shep was creating family ties. "When Shep connects to you, you are sewn to his clothes," Alice says. "You are connected, and you have to do something horrible to be disconnected."

Still, given that he and the kids lived so far apart, their relationship played out mostly during the holidays and summer vacation—until Amber, at 11 years old and looking to attend boarding school near someone she knew, chose one in Hawaii.

Though Winona kept inviting Shep to come an visit, he always had an excuse. But then, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, the resistance fell away. Part of it was the kids' innocence—the same thing that had drawn him to Mia; part of it was this unexpected chance to redo his own past. "I woke up one day," Shep remembers, "and said, 'Let me get my childhood back with these guys." A door opened—he had an idea. "I called up Winona and said, 'Do you think everybody would like to go to Disney World?'" Shep says. "She said, 'Are you kidding?' I'd never been to Disney World, and I always wanted to go. And I couldn't imagine a better way than with four kids."

Before setting off for Orlando, however, Shep had to properly introduce himself. Ever the showman, he arrived at the kids' front door wearing a Rasta wig.

It could have backfired, but once the children recovered from the ridiculous sight, they all laughed and welcomed this large, silly, incredibly important man into their lives.

Says Winona, "The showing up was the commitment: 'Okay, he's here.' Thus, the journey begins. The 18-year journey."

Henceforth, the Champagne-swilling hotshot would be known as Grandpa Shep.

In the beginning, none of us thought about being married, none of us thought about having kids," says Alice Cooper, propping his feet, clad in black boots embossed with a skull and crossbones, on the coffee table in his suite at New York's Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. He's here rehearsing for the next night's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, during which he and his former band will be inducted. The familiar, stringy dyed-black ultra-shag frames his open, amused, middle-aged face; with different hair and clothes he could be selling insurance. "All we cared about was where the next show was, and is there gonna be beer there. :ater on when we got past the insanity of the rock star thing, it was suddenly, 'Okay, now we have to start controlling this lifestyle because we want to live through it.' That's when people starting getting interested in settling down." In 1975 Cooper met Sheryl Goddard, a ballet-trained dancer on his Welcome to My Nightmare tour; they've been married 35 years, surviving Cooper's battle with alcohol, among other things, and have three kids, ages 19, 26, and 30.

When the children were little, in the early '90s, they magically acquired four instant "cousins" in the form of Shep's kids. "I had Amber on one hip, my daughter on the other hip, and they were just my own," says Sheryl Cooper. The rambling clans—Winona and sometimes her mother included—vacationed together. "We spent a lot of time in Hawaii, down in Florida at Disney World, Europe," says Alice. ("Yeah, we did all that family stuff," Shep says later, with a proud, contented chuckle.) "His kids came on tour. The band had a bus and Shep got another bus—I said, 'Great, that'll be the kids' bus.'" Shep made every outing a party, colonizing tables at restaurants and ordering everything on the menu with a wave of his hand. He frequently brought other bold-faced friends into the mix—big-deal guys who seemed both inspired and abashed by what Shep had taken on: When the kids were in Hawaii, former NBA coach Don Nelson ("Uncle Donny") picked them up every day and took them to his home to swim; actor Tom Arnold had a standing game of pool with Amber and once missed a flight in order to fit it in. The only way he knew how, Shep was creating family ties. "When Shep connects to you, you are sewn to his clothes," Alice says. "You are connected, and you have to do something horrible to be disconnected."

Still, given that he and the kids lived so far apart, their relationship played out mostly during the holidays and summer vacation—until Amber, at 11 years old and looking to attend boarding school near someone she knew, chose one in Hawaii.

Alice Cooper backstage with Keira, Amber, and Monique, 2005.

"My initial reaction was, 'Wow, that's scary,'" Shep says. 'She's gonna be my responsibility.' But it was also exciting, because I was alone, basically. I had made the decision early on, when I decided to become emotionally involved with the kids, that I didn't want them coming out every summer seeing a different woman in my life—which fit well into my fear of attachment. It became very convenient."

Amber enrolled in school on the Big Island, taking a puddle jumper back to Shep's house on weekends. "I was doing parents' day, going to wrestling matches—she was a wrestler," Shep says. "It felt so good to be part of a unit. And she gave me so much love. As soon as I really started parenting Amber, I realized, 'This is what I want to do. This makes me happy.'" Soon after, Keira moved to Hawaii, too.

There was a learning curve—like the time Amber said, "Can you take me to the drugstore? Please don't come in." "I had no idea what she was talking about," Shep says. "But with Keira, I was ready: 'Oh, you're buying Tampax?'" The facts-of-life talks were pretty much a bust; while he was driving the girls somewhere, he remembers saying, "'One of my duties is to talk to you about safe sex...' And they just sort of laughed at me." When it was time to shop for school supplies, he'd simply tell the girls they could get whatever they could fit in the cart in 20 minutes. "You should have seen them tearing around," he says with a laugh. "The mall became very important, and there were a lot of trips to Taco Bell."

Now Amber, 23, sweet-faced and joyful, lives with the Coopers while attending Arizona State, where she's a senior. "Clearly, you can look at us and know we're not the norm," she says of her exotic family. "Everywhere Shep and I go, especially in L.A., everyone thinks I'm his young, trashy girlfriend and he's an old creep. We laugh about it. But I am so grateful and blessed. Every girl dreams about her wedding, and I know the day I get married, Alice and Shep are walking me down the aisle."

In some respects, Shep is still feeling his way as a father figure. Recently, Keira, the one who called him Poppy Shep when she was a baby, who spent the better part of her toddler years in his arms, found herself questioning their closeness. Now 20, attending community college in Hawaii, she even wondered if Shep really loved her.

When he heard this, Shep was shocked. "I called her and said, 'Listen, I understand that I'm a horrible communicator,'" he says. "'I'm just not good at human connection. But my intentions are good.'" They talked through some particulars—"and once I heard what she had to say, I understood it completely. Because I don't express myself, and I'm not physical. But we had this beautiful breakthrough, and now we text each other ten times a day."

Amber enrolled in school on the Big Island, taking a puddle jumper back to Shep's house on weekends. "I was doing parents' day, going to wrestling matches—she was a wrestler," Shep says. "It felt so good to be part of a unit. And she gave me so much love. As soon as I really started parenting Amber, I realized, 'This is what I want to do. This makes me happy.'" Soon after, Keira moved to Hawaii, too.

There was a learning curve—like the time Amber said, "Can you take me to the drugstore? Please don't come in." "I had no idea what she was talking about," Shep says. "But with Keira, I was ready: 'Oh, you're buying Tampax?'" The facts-of-life talks were pretty much a bust; while he was driving the girls somewhere, he remembers saying, "'One of my duties is to talk to you about safe sex...' And they just sort of laughed at me." When it was time to shop for school supplies, he'd simply tell the girls they could get whatever they could fit in the cart in 20 minutes. "You should have seen them tearing around," he says with a laugh. "The mall became very important, and there were a lot of trips to Taco Bell."

Now Amber, 23, sweet-faced and joyful, lives with the Coopers while attending Arizona State, where she's a senior. "Clearly, you can look at us and know we're not the norm," she says of her exotic family. "Everywhere Shep and I go, especially in L.A., everyone thinks I'm his young, trashy girlfriend and he's an old creep. We laugh about it. But I am so grateful and blessed. Every girl dreams about her wedding, and I know the day I get married, Alice and Shep are walking me down the aisle."

In some respects, Shep is still feeling his way as a father figure. Recently, Keira, the one who called him Poppy Shep when she was a baby, who spent the better part of her toddler years in his arms, found herself questioning their closeness. Now 20, attending community college in Hawaii, she even wondered if Shep really loved her.

When he heard this, Shep was shocked. "I called her and said, 'Listen, I understand that I'm a horrible communicator,'" he says. "'I'm just not good at human connection. But my intentions are good.'" They talked through some particulars—"and once I heard what she had to say, I understood it completely. Because I don't express myself, and I'm not physical. But we had this beautiful breakthrough, and now we text each other ten times a day."

Shep has no illusions about his life, or anyone else's, suddenly being perfect. he knows he and the kids are on a journey, doing the best they can. In the meantime, the L word flies. "We say it so much," Shep says: "'I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you...' Every communication, every text. It feels so good every time I read it.

When he was a younger man, Shep Gordon didn't imagine his future self as a dude on the loose, a bachelor extraordinaire. "It was never a vision of me sitting at a bar watching a football game," he says. "For me it was like, 'I'd love to pick a tomato from the garden with my kid and go eat it.' But I didn't have the kid or the garden." Nor could he even imagine how to attain such things, given his jaundiced impression of family, growing up. But Shep loved the fantasy, which might explain his obsession with the wholesomeness of Norman Rockwell, whose work he collects. "I've been to his museum in Massachusetts probably a hundred times," he says. "I love that innocence." Even his brief marriage to the Playboy Playmate had something tender at the core. "I really liked her—nice lady—but I thought she was pregnant, an that's really why we got married." In other words, he wanted kids.

Retired now except for one client, Alice Cooper, Shep spends most of his time at home in Maui with the view of Lanai and the high-drama sunsets; during the migratory season, humpback whales swim right past the house. Full of Balinese art and bamboo, it's a perfect place to be barefoot, to entertain, and to cook: During yet another chapter in his page-turner career, Shep minted the concept of the celebrity chef—turning his culinary mentor, Roger Vergé, along with Wolfgang Puck, Emeril Lagasse, and others into the A-list personalities they are now. Last September he was inducted into the Hawaii Restaurant Association's Hall of Fame for helping found the Hawaiian regional cuisine movement, which made dishes like seared ahi seem as accessible as mac and cheese.

Six years ago, at age 60, Shep gave marriage another spin, having fallen for raw food enthusiast and author Renée Loux, 30 years his junior. But even with a blessing from his friend the Dalai Lama, the union lasted only four years.

The Williams kids, though—they're forever. "I think the beauty of what we have is that there's no rules for what makes a family," Shep says. "We became a family in whatever way we could."

Someone says to him flatly, "You saved those kids' lives."

He looks almost surprised by the notion.

"No," Shep says, "they saved mine."

More Stories About Family

When he was a younger man, Shep Gordon didn't imagine his future self as a dude on the loose, a bachelor extraordinaire. "It was never a vision of me sitting at a bar watching a football game," he says. "For me it was like, 'I'd love to pick a tomato from the garden with my kid and go eat it.' But I didn't have the kid or the garden." Nor could he even imagine how to attain such things, given his jaundiced impression of family, growing up. But Shep loved the fantasy, which might explain his obsession with the wholesomeness of Norman Rockwell, whose work he collects. "I've been to his museum in Massachusetts probably a hundred times," he says. "I love that innocence." Even his brief marriage to the Playboy Playmate had something tender at the core. "I really liked her—nice lady—but I thought she was pregnant, an that's really why we got married." In other words, he wanted kids.

Retired now except for one client, Alice Cooper, Shep spends most of his time at home in Maui with the view of Lanai and the high-drama sunsets; during the migratory season, humpback whales swim right past the house. Full of Balinese art and bamboo, it's a perfect place to be barefoot, to entertain, and to cook: During yet another chapter in his page-turner career, Shep minted the concept of the celebrity chef—turning his culinary mentor, Roger Vergé, along with Wolfgang Puck, Emeril Lagasse, and others into the A-list personalities they are now. Last September he was inducted into the Hawaii Restaurant Association's Hall of Fame for helping found the Hawaiian regional cuisine movement, which made dishes like seared ahi seem as accessible as mac and cheese.

Six years ago, at age 60, Shep gave marriage another spin, having fallen for raw food enthusiast and author Renée Loux, 30 years his junior. But even with a blessing from his friend the Dalai Lama, the union lasted only four years.

The Williams kids, though—they're forever. "I think the beauty of what we have is that there's no rules for what makes a family," Shep says. "We became a family in whatever way we could."

Someone says to him flatly, "You saved those kids' lives."

He looks almost surprised by the notion.

"No," Shep says, "they saved mine."

More Stories About Family

Photo: Courtesty of Winona Williams