Looking for Stillness

Photo: Mackenzie Stroh

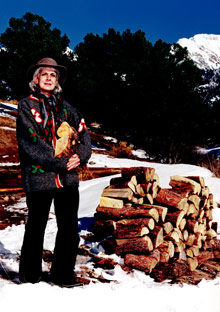

Life: mushy-gray. Spirit: empty. Solution: get back in touch with God. Beverly Donofrio took off six months to go monastery-hopping, and discovered peace, clarity, connection, grace, and, finally, a kind of hush all over her world.

Two winters ago the world turned flat and tuneless on me, and it made no sense. Home was a lively, supportive expat community in an old colonial town in Mexico. I soaked in hot springs, hiked, practiced tai chi, wrote during the day, and spent most of my nights with friends. There were dinners, concerts, readings, margaritas watching the sunset, but it had all gone gray.Not too long before, I could tap into a presence, a feeling of love—some would call it spirit, I called it God. I'd become one of those lucky people who knew as sure as the moon gets full that God exists and is in me and everyone else. But I couldn't sense the presence anymore. I meditated three times a day and felt no peace. I wasn't bored, exactly; it went deeper than that. I needed a God infusion. And so, while visiting my 8-month-old grandson in Brooklyn and needing to be alone to meet a deadline on a book, I had an inspiration. I wrote to the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut, a monastery of 40 Benedictine nuns who run a working farm on 400 acres, and requested a retreat. They wrote back immediately, offering two days.

Turning into the driveway, I spotted my first nun, speeding by in a pickup, a sweatband over her wimple, and something about that incongruity, about observing ancient practices in a speeding world, about working the land, praying with song, practicing silence, living on a commune and never leaving, quickened a longing in me.

For three services a day I sat in the chapel and observed the nuns behind a wrought-iron grill, chanting the hours in Latin. I felt the envy I used to feel in junior high school when I pored over the pictures in my brother's high school yearbook. I wanted to skip from layperson and observer to contemplative singing praises to God with my sisters.

Between chapel visits, I did manage to almost finish my book draft and to plant 200 lilies in the forest. The carpet of leaves soaked my knees, and birds twittered above me, as I buried each bulb thinking about stasis and new life, stagnation and transformation, dark nights and how they too can bloom—into holy joy.

I was aware of how I tend to imagine the future through rosy-colored glasses; high school, after all, had turned out to be closer to hell than heaven. Still, to test the waters once I was back in Brooklyn, I told my son how attracted I'd been to the monastery, and wondered what he thought about the possibility of my joining a place where I'd be cloistered—where he could visit me but I'd rarely be able to visit him. He put his hand on the counter to steady himself. "You know I'll feel abandoned," he said. "You won't see Zach graduate. You won't come to his wedding."

Most sadhus, or holy men, in India have had careers and families, but toward the end of their lives they leave it all to walk the path of enlightenment. Christ said a few times in a few different ways that you must be willing to give up everything, not only your riches but your family, too. You must lose your life to gain it. I understood how one must make God the focus, the ground zero of your being. But I also understood that God is love and doubted that he would ask me to abandon my grandson and my only child, who had no other parent.

I went back home and was distraught to find how lonely I felt despite my busy social world. The contemplative nun fantasies began to bombard me nonstop. Wearing a habit definitely factored in, which probably had something to do with my brother winning a nun doll at a local TV clown show when I was 8 and his refusing to give it to me. (I can still picture the little pearly beads on her rosary belt.) Plus, if I never had to sit for another expensive haircut in my life I'd be ecstatic. Did I really want to pick up another Vogue to gauge the length of hemlines this season—ever again?