Overhelpers Anonymous

If you’re always lending a hand, a shoulder, an ear, even a buck or two to people who can perfectly well solve their own problems, Martha Beck wants you to get over your rescuing addiction and start taking care of yourself.

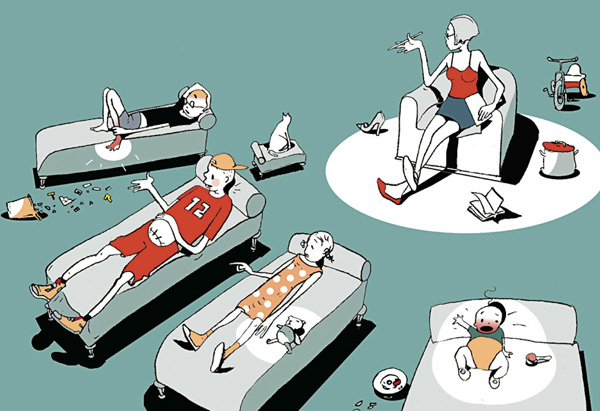

Illustration: Istvan Banyai

Michelle and I met for coffee not long after her youngest child headed off to college. She said she'd been roaming around her empty nest, assembling care packages for her kids, ironing her husband's socks. I clucked sympathetically and reached for my iced coffee when Michelle beat me to it. She reached across the table, grabbed my glass, lifted it a couple of inches, and handed it to me. A few minutes later, she did it again. Then again. After the third time, I said, "Um, Michelle, could you not do that?"

"Oh, I'm so sorry," she said—and reached across the table to hand me my glass again. Then the two of us laughed, as friends will when one of them appears to be possessed, because we both knew what was happening. Michelle had entered a zone we call overhelping. I know that I do the same thing when I'm stressed-out or upset. Maybe you do, too. We get stuck in help mode, draining our own energy, annoying friends, creating weakness and dependency in family members. If this complex sounds all too familiar to you, the following information may be, uh, helpful.

My friend Michelle began ironing socks and treating me like a toddler because taking care of other people, while taxing, eased her anxiety like a hit of opium. Literally.

When my first baby was born, I knew my body would start secreting oxytocin, which stimulates lactation. This seemed weird but logical. What I hadn't expected was the number oxytocin would do on my emotions. I was desperate to feed, pat, carry, diaper, caress, and rock anything that seemed to need help—my baby, certainly, but also my hamster, my local TV news anchorperson, and my broken toaster. When I wasn't doing something helpful, I'd get almost frantic.

These reactions probably evolved so that mothers would care for their babies even at risk to themselves. But all women, not just mothers, secrete oxytocin under pressure. For decades, the famous fight-or-flight response (mediated by hormones like adrenaline) was primarily studied in men. Only in the past six years have researchers found that in women the fight-or-flight response is tempered by a rush of oxytocin, the "tend and befriend" hormone. When things go wrong, we may fight or flee, but also feel strong urges to support and comfort others.

When we actually can help, by rocking the baby, cheering a friend, fixing the ailing toaster, we get a hit of "endogenous opioids," internally produced chemicals that affect our brains like opium. These create a fine, floaty, glowy feeling, one of the main reasons I enjoy being a girl. It's also why I do life coaching (I get paid to get high!), and why Michelle couldn't stop picking up my 12-ounce glass of coffee. Both of us like to self-medicate with the helper hormone.

The Fix: Turning Helper Hormones on Yourself

Therapists and self-help books constantly advise us to get manicures, pedicures, massages, and spa treatments. This advice has a solid biological basis. Any nurturing we direct toward ourselves, especially if it involves physical touch, triggers the same endogenous-opioid surge we get from doing things for others. If you're a hormonal overhelper, schedule a foot rub from a reflexologist, lure your mate into bed, pet the cat until it purrs in your lap. Get touched.

Be especially diligent about this in times of stress. Overhelpers may offer assistance to get a "fix" when they themselves need comfort. This is a quick trip to exhaustion and resentment. The next time you're upset, instead of focusing on trying to help others, pat your own hand and tell yourself kind things ("It's okay, sweetie, the hamster doesn't hate you. He bit you only because he didn't need you to diaper him"). The more you place your full attention on giving yourself comfort, the less you'll help others who don't want it.

"Oh, I'm so sorry," she said—and reached across the table to hand me my glass again. Then the two of us laughed, as friends will when one of them appears to be possessed, because we both knew what was happening. Michelle had entered a zone we call overhelping. I know that I do the same thing when I'm stressed-out or upset. Maybe you do, too. We get stuck in help mode, draining our own energy, annoying friends, creating weakness and dependency in family members. If this complex sounds all too familiar to you, the following information may be, uh, helpful.

Variant #1: Hormonal Helpfulness

My friend Michelle began ironing socks and treating me like a toddler because taking care of other people, while taxing, eased her anxiety like a hit of opium. Literally.

When my first baby was born, I knew my body would start secreting oxytocin, which stimulates lactation. This seemed weird but logical. What I hadn't expected was the number oxytocin would do on my emotions. I was desperate to feed, pat, carry, diaper, caress, and rock anything that seemed to need help—my baby, certainly, but also my hamster, my local TV news anchorperson, and my broken toaster. When I wasn't doing something helpful, I'd get almost frantic.

These reactions probably evolved so that mothers would care for their babies even at risk to themselves. But all women, not just mothers, secrete oxytocin under pressure. For decades, the famous fight-or-flight response (mediated by hormones like adrenaline) was primarily studied in men. Only in the past six years have researchers found that in women the fight-or-flight response is tempered by a rush of oxytocin, the "tend and befriend" hormone. When things go wrong, we may fight or flee, but also feel strong urges to support and comfort others.

When we actually can help, by rocking the baby, cheering a friend, fixing the ailing toaster, we get a hit of "endogenous opioids," internally produced chemicals that affect our brains like opium. These create a fine, floaty, glowy feeling, one of the main reasons I enjoy being a girl. It's also why I do life coaching (I get paid to get high!), and why Michelle couldn't stop picking up my 12-ounce glass of coffee. Both of us like to self-medicate with the helper hormone.

The Fix: Turning Helper Hormones on Yourself

Therapists and self-help books constantly advise us to get manicures, pedicures, massages, and spa treatments. This advice has a solid biological basis. Any nurturing we direct toward ourselves, especially if it involves physical touch, triggers the same endogenous-opioid surge we get from doing things for others. If you're a hormonal overhelper, schedule a foot rub from a reflexologist, lure your mate into bed, pet the cat until it purrs in your lap. Get touched.

Be especially diligent about this in times of stress. Overhelpers may offer assistance to get a "fix" when they themselves need comfort. This is a quick trip to exhaustion and resentment. The next time you're upset, instead of focusing on trying to help others, pat your own hand and tell yourself kind things ("It's okay, sweetie, the hamster doesn't hate you. He bit you only because he didn't need you to diaper him"). The more you place your full attention on giving yourself comfort, the less you'll help others who don't want it.