Great Moments in Mothering

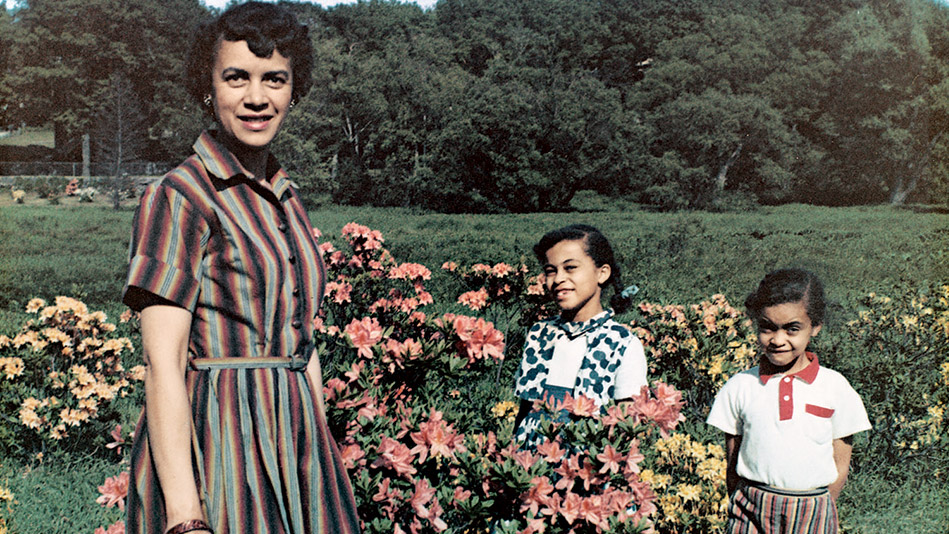

Photo: Courtesy of Patricia Williams

PAGE 7

Meat, Potatoes, Books

by Patricia J. Williams

In the late 1950s, my father took a job quite far from our house. My little sister and I would be practically ready for bed by the time he got home, so my mother would feed us first, delaying her own dinner to eat with him.

I remember this as a major disruption. There had been no more consecrated part of family life than the evening meal, and my parents were very old-fashioned about it. We children were to listen to the adults converse and to ponder the meaning of grown-up topics. If we had thoughts to contribute, we were to express them formally and politely. "Dining with the queen" was my mother's expression for it, and my sister and I warmed to the image. We would fluff ourselves up as though for a tea party, stick out our pinkies, and dab at the corners of our lips with our napkins in mock propriety. "Dining with the dean" was my father's way of inspiring us when we forgot we were dining with the queen. My father's "dean" was a glowering martinet who was miserably judgmental of children who sulked at lima beans or slid too far down in their chairs. (After 30 years in academia, I still have quivers of irrational panic at dinners with the real thing. It's hard to act like a grown-up with that voice in my head: Is that how you'd behave at the dean's table?)

When my father went off to his faraway job, however, we missed the grumpy old dean. There was no buzz of adult conversation under whose radar to daydream. It was a hard time for my mother, I think—my grandmother had died recently, there wasn't much money, and my father was worn out from travel. My mother says she realized she had to fill the silence with something that would keep family time from fragmenting under the weight of her melancholy and the squabbling of two very young children. She began to read aloud to us while we ate, starting with the collected works of Charles Dickens before moving on to Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe.

My mother was very expressive when she read, and in retrospect revealed herself in much deeper ways than I appreciated at the time. She is not someone who would ever tell a joke, for example, but she turned out to be wickedly funny when reading, with a musician's ear for accents. I do not know if I would ever have seen the range of her personality but for the degree to which she breathed dazzle and depth into fictional beings. She gave us a way to read her moods as well, for much of the drama emanated not from the page but from her heart. If things were going well, the lighthearted characters were crackling. When she wasn't so happy, we sobbed as star-crossed heroines flung themselves into the Thames.

Those dinners became for me like Proust's madeleine, albeit through the filter of the Betty Crocker Cookbook. I ate canned green bean casserole imagining it was suet pudding; wedges of iceberg lettuce with Wish-Bone dressing pretending they were leeks. (Years later when I finally tasted a leek, I found myself longing for lettuce.) And when Nicholas Nickelby was forced to ingest treacle and brimstone, my own struggle to consume fried liver and stewed codfish balls was graced with the virtue of empathy.

My mother is in her late 80s now. She says she is pleased that my sister and I have carried on something of the tradition, even though much of the reading is done by books on tape as we ferry her grandchildren from hither to yon. But I do think that her lovely, languid, leisurely mealtime practice made both my sister and me lifelong readers and writers. This Mother's Day, I am sending her a high-tech thank-you note: a CD of me speaking these words. My sister will join me in frying the liver, stewing the cod.

Patricia J. Williams is the author of Open House: Of Family, Friends, Food, Piano Lessons, and the Search for a Room of My Own.

The Next Great Moment in Mothering: Madeleine Albright on what it takes to learn to fly

by Patricia J. Williams

In the late 1950s, my father took a job quite far from our house. My little sister and I would be practically ready for bed by the time he got home, so my mother would feed us first, delaying her own dinner to eat with him.

I remember this as a major disruption. There had been no more consecrated part of family life than the evening meal, and my parents were very old-fashioned about it. We children were to listen to the adults converse and to ponder the meaning of grown-up topics. If we had thoughts to contribute, we were to express them formally and politely. "Dining with the queen" was my mother's expression for it, and my sister and I warmed to the image. We would fluff ourselves up as though for a tea party, stick out our pinkies, and dab at the corners of our lips with our napkins in mock propriety. "Dining with the dean" was my father's way of inspiring us when we forgot we were dining with the queen. My father's "dean" was a glowering martinet who was miserably judgmental of children who sulked at lima beans or slid too far down in their chairs. (After 30 years in academia, I still have quivers of irrational panic at dinners with the real thing. It's hard to act like a grown-up with that voice in my head: Is that how you'd behave at the dean's table?)

When my father went off to his faraway job, however, we missed the grumpy old dean. There was no buzz of adult conversation under whose radar to daydream. It was a hard time for my mother, I think—my grandmother had died recently, there wasn't much money, and my father was worn out from travel. My mother says she realized she had to fill the silence with something that would keep family time from fragmenting under the weight of her melancholy and the squabbling of two very young children. She began to read aloud to us while we ate, starting with the collected works of Charles Dickens before moving on to Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe.

My mother was very expressive when she read, and in retrospect revealed herself in much deeper ways than I appreciated at the time. She is not someone who would ever tell a joke, for example, but she turned out to be wickedly funny when reading, with a musician's ear for accents. I do not know if I would ever have seen the range of her personality but for the degree to which she breathed dazzle and depth into fictional beings. She gave us a way to read her moods as well, for much of the drama emanated not from the page but from her heart. If things were going well, the lighthearted characters were crackling. When she wasn't so happy, we sobbed as star-crossed heroines flung themselves into the Thames.

Those dinners became for me like Proust's madeleine, albeit through the filter of the Betty Crocker Cookbook. I ate canned green bean casserole imagining it was suet pudding; wedges of iceberg lettuce with Wish-Bone dressing pretending they were leeks. (Years later when I finally tasted a leek, I found myself longing for lettuce.) And when Nicholas Nickelby was forced to ingest treacle and brimstone, my own struggle to consume fried liver and stewed codfish balls was graced with the virtue of empathy.

My mother is in her late 80s now. She says she is pleased that my sister and I have carried on something of the tradition, even though much of the reading is done by books on tape as we ferry her grandchildren from hither to yon. But I do think that her lovely, languid, leisurely mealtime practice made both my sister and me lifelong readers and writers. This Mother's Day, I am sending her a high-tech thank-you note: a CD of me speaking these words. My sister will join me in frying the liver, stewing the cod.

Patricia J. Williams is the author of Open House: Of Family, Friends, Food, Piano Lessons, and the Search for a Room of My Own.

The Next Great Moment in Mothering: Madeleine Albright on what it takes to learn to fly