Great Moments in Mothering

We asked eight women to tell us about their mothers' greatest hits—lessons learned, love made visible, childhood tears turned to still-glowing triumph. These are their stories.

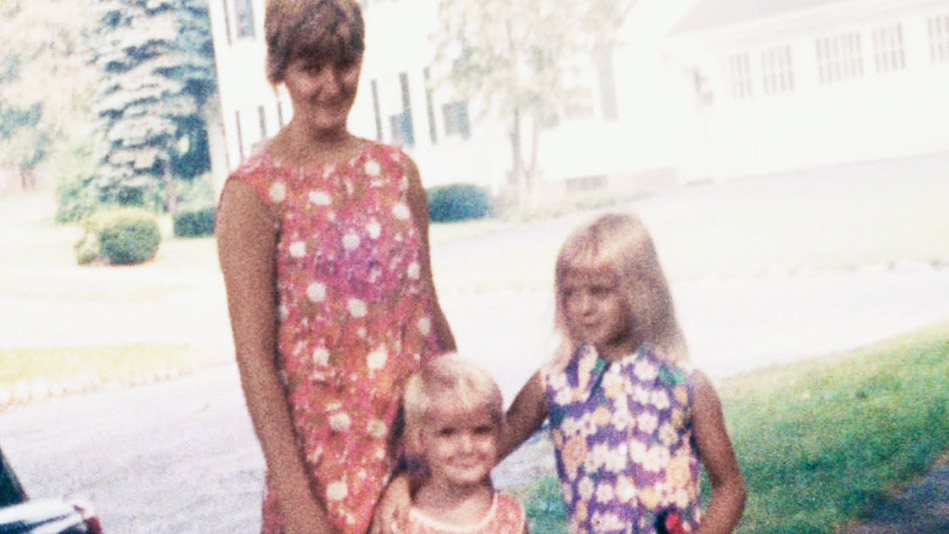

Photo: Courtesy of Elizabeth Gilbert

How to Steal a Show

by Elizabeth Gilbert

When I was in the third grade, our class put on a play called The Lemonade Stand. Which told the story of, well, a lemonade stand. Which featured three little girls spending a lot of time waiting for something to happen. Which may sound like an avant-garde Samuel Beckett production but was actually just one of those generic plays written for third-graders, wherein all 25 kids in the class get to say at least one line. Except for the three female leads, who, naturally, get to be onstage, selling lemonade, and speaking the whole time.

Now, I don't want to boast, but I was a formidable performer back in the third grade. My older sister and I had already produced dozens of plays in our living room, and my voice was capable of projecting power-fully across the school auditorium (and everywhere else, I'm afraid), so there was no question in my mind that I was a natural choice for one of the leading roles. Nonetheless, show business is a cruel mistress and I did not get cast as one of the starring lemonade girls. What I got instead was the part of Mrs. Fields—the only adult character in the play. Surely this made sense to Mrs. Domino (the director of this production) because I was about 11 inches taller than everyone else my age. Fine, except that Mrs. Fields was one of the smallest roles. Mrs. Fields had exactly two lines.

Was I angry? No—I was shattered. And in my sorrow, I did something so completely out of character that I still can't really believe it myself: I walked up to Mrs. Domino and basically told her where she could stick her stupid play. And then I quit the stupid play. And then I sobbed for approximately the next seven hours.

This is where my mother comes in. Such moments of high distress are true tests of parenting. My mother is not a saint or a paragon; she's just a woman who, like many mothers, tried to do her best with her kids, sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding. But this was the moment of my life where she succeeded perhaps most brilliantly, where she really did it right.

First of all—what she didn't do: She didn't charge into the principal's office demanding that her daughter be given a better part, nor did she congratulate me on having quit the play, saying, "Yeah, screw Mrs. Domino." She never indicated that the three-headed monster shouldn't have been given the starring role, nor did she allow my letdown to feed her own insecurities, worrying that her child (therefore, she herself) was a failure. And, of course, she'd never have dreamed of scorning my sorrow with a comment like "Buck up, kiddo—crap happens. Now go get Mommy another beer."

What Elizabeth Gilbert learned on the stage of life

by Elizabeth Gilbert

When I was in the third grade, our class put on a play called The Lemonade Stand. Which told the story of, well, a lemonade stand. Which featured three little girls spending a lot of time waiting for something to happen. Which may sound like an avant-garde Samuel Beckett production but was actually just one of those generic plays written for third-graders, wherein all 25 kids in the class get to say at least one line. Except for the three female leads, who, naturally, get to be onstage, selling lemonade, and speaking the whole time.

Now, I don't want to boast, but I was a formidable performer back in the third grade. My older sister and I had already produced dozens of plays in our living room, and my voice was capable of projecting power-fully across the school auditorium (and everywhere else, I'm afraid), so there was no question in my mind that I was a natural choice for one of the leading roles. Nonetheless, show business is a cruel mistress and I did not get cast as one of the starring lemonade girls. What I got instead was the part of Mrs. Fields—the only adult character in the play. Surely this made sense to Mrs. Domino (the director of this production) because I was about 11 inches taller than everyone else my age. Fine, except that Mrs. Fields was one of the smallest roles. Mrs. Fields had exactly two lines.

Was I angry? No—I was shattered. And in my sorrow, I did something so completely out of character that I still can't really believe it myself: I walked up to Mrs. Domino and basically told her where she could stick her stupid play. And then I quit the stupid play. And then I sobbed for approximately the next seven hours.

This is where my mother comes in. Such moments of high distress are true tests of parenting. My mother is not a saint or a paragon; she's just a woman who, like many mothers, tried to do her best with her kids, sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding. But this was the moment of my life where she succeeded perhaps most brilliantly, where she really did it right.

First of all—what she didn't do: She didn't charge into the principal's office demanding that her daughter be given a better part, nor did she congratulate me on having quit the play, saying, "Yeah, screw Mrs. Domino." She never indicated that the three-headed monster shouldn't have been given the starring role, nor did she allow my letdown to feed her own insecurities, worrying that her child (therefore, she herself) was a failure. And, of course, she'd never have dreamed of scorning my sorrow with a comment like "Buck up, kiddo—crap happens. Now go get Mommy another beer."

What Elizabeth Gilbert learned on the stage of life