Oprah Honors Freedom Riders

Photo: Library of Congress

The year was 1961. John F. Kennedy was sworn in as America's 35th president, and the Camelot era was, for many, a time of hope and optimism. That same year, the United States put its first man into space, and popular TV shows like Leave It to Beaver and The Andy Griffith Show depicted the all-American life.

But those idyllic images were not reflective of life for many African-Americans, especially in the Deep South. Despite efforts to end segregation, Jim Crow laws still forced black people to use separate water fountains, public restrooms and waiting rooms. And on buses and trains, black citizens were told to sit in the back.

In 1946 and again in 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed these racist practices, but many white southerners continued to follow their own set of rules.

Then, in the spring and summer of 1961, a courageous coalition of men and women—black and white, young and old—boarded buses in protest of these discriminatory practices. They called themselves the Freedom Riders.

"For many of you watching, I know that this may be the first time you're even hearing about the Freedom Rides, but let me tell you, if it were not for these American heroes, this country would be a very different place right now," Oprah says. "The lives of millions of you watching at home would be dramatically different. I know my life would be were it not for them."

But those idyllic images were not reflective of life for many African-Americans, especially in the Deep South. Despite efforts to end segregation, Jim Crow laws still forced black people to use separate water fountains, public restrooms and waiting rooms. And on buses and trains, black citizens were told to sit in the back.

In 1946 and again in 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed these racist practices, but many white southerners continued to follow their own set of rules.

Then, in the spring and summer of 1961, a courageous coalition of men and women—black and white, young and old—boarded buses in protest of these discriminatory practices. They called themselves the Freedom Riders.

"For many of you watching, I know that this may be the first time you're even hearing about the Freedom Rides, but let me tell you, if it were not for these American heroes, this country would be a very different place right now," Oprah says. "The lives of millions of you watching at home would be dramatically different. I know my life would be were it not for them."

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

Fifty years ago, on May 4, 1961, the Freedom Rides began in Washington, D.C. That day, 13 men and women boarded two buses bound for the Deep South, a region plagued by racial injustice.

The plan was simple. The Freedom Riders would buy tickets on interstate buses for a two-week journey that would end in New Orleans. Along the way, the Riders would test federal laws that prohibited segregation by riding in the front of buses and sitting in waiting rooms designated "whites only" and "colored." It was dangerous and daring—some even considered it a suicide mission.

Retrace the original 1961 Freedom Ride

The movement was organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which trained the Freedom Riders to be nonviolent and protest without ever striking back. They hoped these peaceful demonstrations would force the government to step up and protect their civil rights. Little did they know, the Freedom Riders, which totaled 436 by the end of the movement, would change the course of American history.

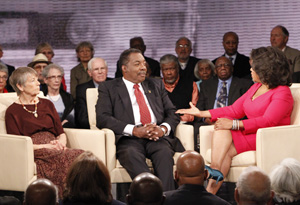

In honor of the 50th anniversary, Oprah has gathered 178 survivors of the Freedom Rides—including 95-year-old George Houser, the last surviving member of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation—together to express her admiration. "As an African-American woman born in Mississippi and raised in the South, I, like so many of you, owe a deep debt of gratitude to the Freedom Riders," she says. "I stand among heroes."

Watch Oprah share the stage with 178 survivors

The plan was simple. The Freedom Riders would buy tickets on interstate buses for a two-week journey that would end in New Orleans. Along the way, the Riders would test federal laws that prohibited segregation by riding in the front of buses and sitting in waiting rooms designated "whites only" and "colored." It was dangerous and daring—some even considered it a suicide mission.

Retrace the original 1961 Freedom Ride

The movement was organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which trained the Freedom Riders to be nonviolent and protest without ever striking back. They hoped these peaceful demonstrations would force the government to step up and protect their civil rights. Little did they know, the Freedom Riders, which totaled 436 by the end of the movement, would change the course of American history.

In honor of the 50th anniversary, Oprah has gathered 178 survivors of the Freedom Rides—including 95-year-old George Houser, the last surviving member of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation—together to express her admiration. "As an African-American woman born in Mississippi and raised in the South, I, like so many of you, owe a deep debt of gratitude to the Freedom Riders," she says. "I stand among heroes."

Watch Oprah share the stage with 178 survivors

Oprah says she was inspired to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides after seeing the PBS documentary Freedom Riders. The film documents the Freedom Riders' journey, which began with intense training.

During these training sessions, CORE members were subjected to staged verbal and physical attacks to prepare them for what was to come. They believed they were ready for anything—even the possibility of death—and their determination to fight for racial equality outweighed all fear and doubt.

Looking back at this moment in American history, Oprah is astounded by their bravery. "I know in my heart, I don't believe I would have had the courage to do what these brave souls did," she says. "I don't believe I would have had the courage to get on those buses."

When the 13 original Freedom Riders boarded their buses, they didn't have security, but they had hope. "Boarding that Greyhound bus to travel to the Deep South, I felt good. I felt happy," says John Lewis, a former Freedom Rider and current U.S. congressman.

The first few days were uneventful, and when the Freedom Riders arrived in Atlanta on May 13, 1961, they attended a reception hosted by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. They hoped this civil rights leader would join their movement, but instead, he passed along an ominous warning. He said the Ku Klux Klan had "quite a welcome" planned for them in Alabama, and he urged them to reconsider their route.

The next day, however, the buses and the Riders rolled on.

During these training sessions, CORE members were subjected to staged verbal and physical attacks to prepare them for what was to come. They believed they were ready for anything—even the possibility of death—and their determination to fight for racial equality outweighed all fear and doubt.

Looking back at this moment in American history, Oprah is astounded by their bravery. "I know in my heart, I don't believe I would have had the courage to do what these brave souls did," she says. "I don't believe I would have had the courage to get on those buses."

When the 13 original Freedom Riders boarded their buses, they didn't have security, but they had hope. "Boarding that Greyhound bus to travel to the Deep South, I felt good. I felt happy," says John Lewis, a former Freedom Rider and current U.S. congressman.

The first few days were uneventful, and when the Freedom Riders arrived in Atlanta on May 13, 1961, they attended a reception hosted by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. They hoped this civil rights leader would join their movement, but instead, he passed along an ominous warning. He said the Ku Klux Klan had "quite a welcome" planned for them in Alabama, and he urged them to reconsider their route.

The next day, however, the buses and the Riders rolled on.

Photo: Getty Images

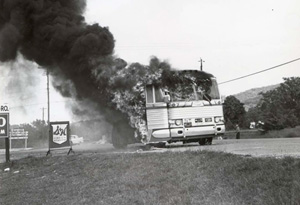

On the 11th day of the ride, two buses left Atlanta one hour apart. Freedom Riders were on both buses, along with regular passengers.

When the first bus crossed the Alabama state line, it was soon surrounded by an angry mob organized by the Ku Klux Klan. In the small town of Anniston, Alabama, approximately 200 men set out to teach the Freedom Riders a lesson.

Using metal pipes, clubs and chains, the crowd attacked the bus, smashing windows and denting the sides. After 15 terrifying minutes, the driver was able to pull away, but he quickly realized someone had slashed the tires.

Panicked, the driver went for help, abandoning the bus and its passengers. Then, something crashed through a window which set the bus ablaze. With their lungs filled with smoke, Freedom Riders and their fellow passengers spilled out onto the grass—and into the hands of the angry mob.

When the first bus crossed the Alabama state line, it was soon surrounded by an angry mob organized by the Ku Klux Klan. In the small town of Anniston, Alabama, approximately 200 men set out to teach the Freedom Riders a lesson.

Using metal pipes, clubs and chains, the crowd attacked the bus, smashing windows and denting the sides. After 15 terrifying minutes, the driver was able to pull away, but he quickly realized someone had slashed the tires.

Panicked, the driver went for help, abandoning the bus and its passengers. Then, something crashed through a window which set the bus ablaze. With their lungs filled with smoke, Freedom Riders and their fellow passengers spilled out onto the grass—and into the hands of the angry mob.

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

Genevieve Hughes Haughton and Hank Thomas are two of the surviving Freedom Riders who were on the bus that was bombed in Alabama. Fifty years later, Hank, who was 19 years old when he signed on to be a Freedom Rider, still remembers that day.

"The mob had pretty much broken out most of the windows. They were trying to get into the door, but fortunately for us, when the bus driver got off of the bus, he locked the door so they couldn't get inside. So for a moment, I thought we were safe," he says. "I knew that if I got off the bus, I knew the mob would kill me."

Everything changed when the fire began. "After a while, I couldn't breathe any longer so I thought it would be a good idea to go to the front of the bus, and maybe there would be some oxygen there," Genevieve says. "We all proceeded forward."

Outside, Hank says the mob was yelling things like, "We're gonna kill these n*****s," and "Let's burn these n*****s alive." So Hank made a choice—he says he tried to commit suicide.

"I thought that if I breathe in the smoke, took a big deep breath of the smoke, it would put me to sleep and that's the way I would die," he says. "When I did, of course, the involuntary actions of your body take over, and you try to fight for air."

Hank ran to the front of the bus with the other passengers, but when they tried to get off, they were trapped. Hank says the mob had blocked the door. Then, at that moment, the bus' fuel tank exploded. "When it exploded, everybody ran, the ones outside, and that's the only way we were able to get off of that bus," Hank says.

"The mob had pretty much broken out most of the windows. They were trying to get into the door, but fortunately for us, when the bus driver got off of the bus, he locked the door so they couldn't get inside. So for a moment, I thought we were safe," he says. "I knew that if I got off the bus, I knew the mob would kill me."

Everything changed when the fire began. "After a while, I couldn't breathe any longer so I thought it would be a good idea to go to the front of the bus, and maybe there would be some oxygen there," Genevieve says. "We all proceeded forward."

Outside, Hank says the mob was yelling things like, "We're gonna kill these n*****s," and "Let's burn these n*****s alive." So Hank made a choice—he says he tried to commit suicide.

"I thought that if I breathe in the smoke, took a big deep breath of the smoke, it would put me to sleep and that's the way I would die," he says. "When I did, of course, the involuntary actions of your body take over, and you try to fight for air."

Hank ran to the front of the bus with the other passengers, but when they tried to get off, they were trapped. Hank says the mob had blocked the door. Then, at that moment, the bus' fuel tank exploded. "When it exploded, everybody ran, the ones outside, and that's the only way we were able to get off of that bus," Hank says.

Throughout the movement, there were southerners—both black and white—who risked their lives to help the Freedom Riders. One of them was a brave seventh grader named Janie Forsyth.

Janie was just 12 years old when the Freedom Riders' bus was firebombed in front of her family's Alabama grocery store. "The door burst open, and people just spilled out into the yard. They were practically tripping over each other because they were so sick," Janie recounts in the documentary Freedom Riders. "It was horrible. It was like a scene from hell. It was the worst suffering I'd ever heard."

A member of the mob hit Hank over the head with a baseball bat, nearly knocking him unconscious, while other Freedom Riders lay on the ground begging for water. Janie, a white girl raised in the segregated South, couldn't take it. "It got to the point where, if they had called them names, I would have done nothing," Janie says. "But it got to the point where they were threatening their lives. They were visiting violence on them. They got past my personal ability to withstand it without trying to do something."

That day, Janie defied the Klan. She says she picked out a woman, washed her face, held her and gave her a glass of water to drink. Then, she picked out someone else to help. Hank was one of those people.

Watch Hank and Janie's emotional reunion

After that day, Janie says she awaited retaliation from the Klan. "I knew it was not a safe thing to defy the Ku Klux Klan," she says. "Eventually, I had heard that they had one of their meetings. ... They had discussed what to do about Richard Forsyth's little girl, Janie. And I found out that in that meeting, some of them had decided to give me a pass because I was young and obviously didn't know what I was doing. [They said] I was 'weak-minded.'"

Hank says he often wondered what happened to the little girl who brought him water. "I thought about her and her bravery and what happened to her afterwards, so when I saw her again today, of all of the ugliness and all of the evils that took place on Anniston that day, this was the little angel," he says. "And I will never, ever forget her."

Janie was just 12 years old when the Freedom Riders' bus was firebombed in front of her family's Alabama grocery store. "The door burst open, and people just spilled out into the yard. They were practically tripping over each other because they were so sick," Janie recounts in the documentary Freedom Riders. "It was horrible. It was like a scene from hell. It was the worst suffering I'd ever heard."

A member of the mob hit Hank over the head with a baseball bat, nearly knocking him unconscious, while other Freedom Riders lay on the ground begging for water. Janie, a white girl raised in the segregated South, couldn't take it. "It got to the point where, if they had called them names, I would have done nothing," Janie says. "But it got to the point where they were threatening their lives. They were visiting violence on them. They got past my personal ability to withstand it without trying to do something."

That day, Janie defied the Klan. She says she picked out a woman, washed her face, held her and gave her a glass of water to drink. Then, she picked out someone else to help. Hank was one of those people.

Watch Hank and Janie's emotional reunion

After that day, Janie says she awaited retaliation from the Klan. "I knew it was not a safe thing to defy the Ku Klux Klan," she says. "Eventually, I had heard that they had one of their meetings. ... They had discussed what to do about Richard Forsyth's little girl, Janie. And I found out that in that meeting, some of them had decided to give me a pass because I was young and obviously didn't know what I was doing. [They said] I was 'weak-minded.'"

Hank says he often wondered what happened to the little girl who brought him water. "I thought about her and her bravery and what happened to her afterwards, so when I saw her again today, of all of the ugliness and all of the evils that took place on Anniston that day, this was the little angel," he says. "And I will never, ever forget her."

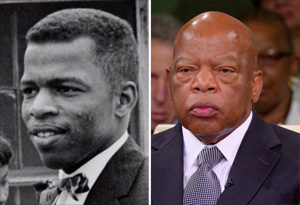

United States Congressman John Lewis was a prominent figure in the civil rights movement who once worked side by side with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But before he marched on Washington in 1963, he was a 21-year-old seminary student who left school to become a Freedom Rider.

On May 9, 1961, when Rep. Lewis stepped off the bus and into a South Carolina bus terminal, he says he was attacked by an angry white man.

"My seatmate was a young white gentleman by the name of Albert Bigelow, and the moment we stepped off the bus, we attempted to enter a so-called white waiting room," he says. "And a group of young men came toward us and started beating us. I was beaten and left bloody."

Throughout the beating, Rep. Lewis, a man raised in the segregated South, never raised a fist. How did he endure the violence? "During the time I was being beaten and other times when I was being beaten, I had what I called 'an executive session' with myself. I said, 'I'm going to take it. I'm prepared,'" he says. "On the Freedom Ride, I was prepared to die."

Rep. Lewis' passion was fueled by a deep desire to end racial discrimination. "I had grown up seeing those signs," he says. "I didn't like it. I hated those signs that said 'white men,' 'colored women,' 'white waiting,' 'colored waiting.' So I wanted to do something about it."

On May 9, 1961, when Rep. Lewis stepped off the bus and into a South Carolina bus terminal, he says he was attacked by an angry white man.

"My seatmate was a young white gentleman by the name of Albert Bigelow, and the moment we stepped off the bus, we attempted to enter a so-called white waiting room," he says. "And a group of young men came toward us and started beating us. I was beaten and left bloody."

Throughout the beating, Rep. Lewis, a man raised in the segregated South, never raised a fist. How did he endure the violence? "During the time I was being beaten and other times when I was being beaten, I had what I called 'an executive session' with myself. I said, 'I'm going to take it. I'm prepared,'" he says. "On the Freedom Ride, I was prepared to die."

Rep. Lewis' passion was fueled by a deep desire to end racial discrimination. "I had grown up seeing those signs," he says. "I didn't like it. I hated those signs that said 'white men,' 'colored women,' 'white waiting,' 'colored waiting.' So I wanted to do something about it."

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

Elwin Wilson says he knows exactly what happened to Rep. Lewis that day because he is the man who beat him. After years of regret, Elwin apologized to the congressman in 2009, and today, Elwin speaks out against bigotry and intolerance. "I know this takes a lot of courage on your part to show your face to the world and to say, 'I am the man who beat you,'" Oprah says.

For years, Elwin, an admitted former member of the Ku Klux Klan, says he prayed that he would meet the man he attacked at the bus station.

"What happened was, after he was beat and bloody and all, the policeman came up and asked him, he said, 'Do y'all want to take out warrants? [Press] charges,'" Elwin says. "He said, 'No.' He said, 'We're not here to cause trouble.' He said, 'We're here for people to love each other.'"

Rep. Lewis' decision not to press charges and his declaration of peace struck Elwin. "The thought, it come in my mind so many times, what he said he wasn't out to harm nobody," Elwin says.

When Elwin came to the congressman's office in 2009, the two men made amends. "He said, 'I attacked you, and I'm sorry. I want to apologize. Will you accept my apology?' And I said, 'Yes.' And he gave me a hug, and he started crying. I hugged him back, and I shed some tears also," Rep. Lewis says. "He's the first and only person who has ever apologized to me."

For years, Elwin, an admitted former member of the Ku Klux Klan, says he prayed that he would meet the man he attacked at the bus station.

"What happened was, after he was beat and bloody and all, the policeman came up and asked him, he said, 'Do y'all want to take out warrants? [Press] charges,'" Elwin says. "He said, 'No.' He said, 'We're not here to cause trouble.' He said, 'We're here for people to love each other.'"

Rep. Lewis' decision not to press charges and his declaration of peace struck Elwin. "The thought, it come in my mind so many times, what he said he wasn't out to harm nobody," Elwin says.

When Elwin came to the congressman's office in 2009, the two men made amends. "He said, 'I attacked you, and I'm sorry. I want to apologize. Will you accept my apology?' And I said, 'Yes.' And he gave me a hug, and he started crying. I hugged him back, and I shed some tears also," Rep. Lewis says. "He's the first and only person who has ever apologized to me."

After several days of bloodshed, the Freedom Riders were stranded in Alabama. No bus drivers were willing to take them any further, and they were surrounded by a hostile, racist mob—the Freedom Rides were over.

Southern white supremacists thought they had won, but they didn't know about Diane Nash, a soft-spoken force to be reckoned with. Diane was a leader of the Nashville Student Movement in 1961. "It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence," Diane says. "It was critical that the Freedom Ride not stop, and that it be continued immediately."

On her 23rd birthday, Diane agreed to coordinate a second wave of Freedom Rides, keeping the movement alive. "We were fresh troops," Diane says.

In the middle of final exams, 21 students from various Nashville colleges left school to join the fight for equality.

Southern white supremacists thought they had won, but they didn't know about Diane Nash, a soft-spoken force to be reckoned with. Diane was a leader of the Nashville Student Movement in 1961. "It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence," Diane says. "It was critical that the Freedom Ride not stop, and that it be continued immediately."

On her 23rd birthday, Diane agreed to coordinate a second wave of Freedom Rides, keeping the movement alive. "We were fresh troops," Diane says.

In the middle of final exams, 21 students from various Nashville colleges left school to join the fight for equality.

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

When U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy heard that more students were continuing the Freedom Rides, he called his assistant, John Seigenthaler. "My phone in the hotel room rings, and it's the attorney general," John says. "He opens the conversation, 'Who the hell is Diane Nash? Call her and let her know what is waiting for the Freedom Riders.'"

John called Diane to try to stop the Freedom Riders from Nashville, but Diane responded, "They're not going to turn back. They're on their way to Birmingham, and they'll be there shortly."

Fearing for their safety, John pled with Diane, but she told him the students knew of the danger that lay ahead. The night before they left Nashville, Diane told John they signed their last wills and testaments.

Diane says she chose to lead the Nashville Freedom Rides because she'd had enough. "Segregation was so humiliating," she says. "If you went downtown in Nashville during the lunch hour, blacks would be sitting on the curb eating their lunch that they had brought from home or had bought from a restaurant on a take-out basis. It was humiliating, and I hated it."

Every time Diane obeyed a segregation sign, she says she felt like she was agreeing that she was, in fact, inferior. "Too inferior to use the ordinary facility that the general public used," Diane says. "It was a real problem for me."

"Well, I'm glad it was a problem," Oprah says.

John called Diane to try to stop the Freedom Riders from Nashville, but Diane responded, "They're not going to turn back. They're on their way to Birmingham, and they'll be there shortly."

Fearing for their safety, John pled with Diane, but she told him the students knew of the danger that lay ahead. The night before they left Nashville, Diane told John they signed their last wills and testaments.

Diane says she chose to lead the Nashville Freedom Rides because she'd had enough. "Segregation was so humiliating," she says. "If you went downtown in Nashville during the lunch hour, blacks would be sitting on the curb eating their lunch that they had brought from home or had bought from a restaurant on a take-out basis. It was humiliating, and I hated it."

Every time Diane obeyed a segregation sign, she says she felt like she was agreeing that she was, in fact, inferior. "Too inferior to use the ordinary facility that the general public used," Diane says. "It was a real problem for me."

"Well, I'm glad it was a problem," Oprah says.

The Freedom Riders from Nashville eventually made it to Montgomery, Alabama, where Klansmen had been waiting for them all night. When they arrived, a full-scale riot broke out.

John was there representing Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and he too fell victim to the violent mob. "I was hit in the head, and I'd never been knocked unconscious before," John says. "They knocked me down and kicked me under the car, and I woke up 30 minutes later. A policeman finally picked me up."

Days later, the National Guard escorted the Freedom Riders out of Alabama, but there was no feeling of relief as they crossed the border into Mississippi. Mississippi was the state they feared the most.

When the Freedom Riders walked into the whites-only waiting room in the Jackson, Mississippi, bus terminal, they were immediately arrested and eventually sent to Parchman State Prison Farm, the state's notoriously tough prison.

Ross Barnett, the governor of Mississippi, thought this would break the back of the Freedom Rider movement, but he was sorely mistaken. The Freedom Riders filled Parchman with fellow activists and transformed the prison into the next site of the civil rights movement.

John was there representing Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and he too fell victim to the violent mob. "I was hit in the head, and I'd never been knocked unconscious before," John says. "They knocked me down and kicked me under the car, and I woke up 30 minutes later. A policeman finally picked me up."

Days later, the National Guard escorted the Freedom Riders out of Alabama, but there was no feeling of relief as they crossed the border into Mississippi. Mississippi was the state they feared the most.

When the Freedom Riders walked into the whites-only waiting room in the Jackson, Mississippi, bus terminal, they were immediately arrested and eventually sent to Parchman State Prison Farm, the state's notoriously tough prison.

Ross Barnett, the governor of Mississippi, thought this would break the back of the Freedom Rider movement, but he was sorely mistaken. The Freedom Riders filled Parchman with fellow activists and transformed the prison into the next site of the civil rights movement.

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

Ernest "Rip" Patton Jr., Carol Ruth Silver and Congressman Lewis were among the 300 Freedom Riders who spent the summer of 1961 in Parchman Prison.

Watch Rip share his prison experience

Carol Ruth, who was 21 years old at the time, was packed with 22 other girls in a cell built for four before being transferred to Parchman. "There were four bunks, and the rest of us slept on the floor," Carol Ruth says. "We were told, 'They're going to take you to Parchman.' We were really afraid at that point because the reputation of Parchman is that it's a place that a lot of people get sent...and don't come back."

Prison guards tried to punish the Riders by taking away their basic necessities, like toothbrushes and mattresses, but nothing could break their spirits or stop them from singing. "We did a lot of singing, and they didn't like the singing," Rip says. "And every time that they would threaten to do something, we would sing."

In the end, all of the Riders' suffering paid off. On September 22, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued an order that all Jim Crow signs must be removed from bus and rail stations in the South. The Freedom Riders had won.

Watch Rip share his prison experience

Carol Ruth, who was 21 years old at the time, was packed with 22 other girls in a cell built for four before being transferred to Parchman. "There were four bunks, and the rest of us slept on the floor," Carol Ruth says. "We were told, 'They're going to take you to Parchman.' We were really afraid at that point because the reputation of Parchman is that it's a place that a lot of people get sent...and don't come back."

Prison guards tried to punish the Riders by taking away their basic necessities, like toothbrushes and mattresses, but nothing could break their spirits or stop them from singing. "We did a lot of singing, and they didn't like the singing," Rip says. "And every time that they would threaten to do something, we would sing."

In the end, all of the Riders' suffering paid off. On September 22, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued an order that all Jim Crow signs must be removed from bus and rail stations in the South. The Freedom Riders had won.

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

In 2006, 45 years later, Raymond Arsenault was the first historian to write a comprehensive book about the movement: Freedom Riders. Raymond says this is a story that needed to be told. "When I began work on the book about 13 years ago, I wasn't sure that anybody could do full justice to the Freedom Riders' story," Raymond says. "But I had to try. Just the dramatic power of what they accomplished back in 1961."

Read an excerpt from Freedom Riders

"Everybody who dared to get on those buses is a hero and a heroine," Oprah says.

"That's really the story of the Freedom Rides to me," Raymond says.

Stanley Nelson is the filmmaker who wrote, directed and produced the documentary Freedom Riders, which premieres May 16, 2011, on PBS. "The Freedom Riders were a group of young people that set out at great personal risk to make a change, and they did it," Stanley says. "There were forces all lined up against them, but they didn't let anything stop them."

Go backstage with Stanley

Read an excerpt from Freedom Riders

"Everybody who dared to get on those buses is a hero and a heroine," Oprah says.

"That's really the story of the Freedom Rides to me," Raymond says.

Stanley Nelson is the filmmaker who wrote, directed and produced the documentary Freedom Riders, which premieres May 16, 2011, on PBS. "The Freedom Riders were a group of young people that set out at great personal risk to make a change, and they did it," Stanley says. "There were forces all lined up against them, but they didn't let anything stop them."

Go backstage with Stanley

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

The Freedom Riders' courage and strength has not been forgotten. Fifty years after the movement, 40 college students will retrace the first bus route—from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans—beginning on May 4, 2011. Some of the original Freedom Riders are planning to join the students for the anniversary ride.

"On behalf of all of America, may I say you make us proud to call ourselves American. Thank you," Oprah says to the Freedom Riders.

If you're inspired to right a wrong or make a change in your community, start by answering Oprah's questions: "We stand in reverence for what you have done, and we can ask ourselves these questions as we look at the courage that you all showed at such a young age: 'What's wrong with the world? What can we do to change it?'"

More from the show

Why Freedom Riders got on the bus

Author Raymond Arsenault explains the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders: Then and Now

"On behalf of all of America, may I say you make us proud to call ourselves American. Thank you," Oprah says to the Freedom Riders.

If you're inspired to right a wrong or make a change in your community, start by answering Oprah's questions: "We stand in reverence for what you have done, and we can ask ourselves these questions as we look at the courage that you all showed at such a young age: 'What's wrong with the world? What can we do to change it?'"

More from the show

Why Freedom Riders got on the bus

Author Raymond Arsenault explains the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders: Then and Now

Please note that Harpo Productions, Inc., OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network, Discovery Communications LLC and their affiliated companies and entities have no affiliation with and do not endorse those entities or websites referenced above, which are provided solely as a courtesy. Please conduct your own independent investigation (including an investigation as to whether any contributions are tax deductible) before donating to any charity, project or organization. This information is provided for your reference only.