6 Powerful Poetry Collections from New Voices

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet laureate Tracy K. Smith celebrates a transformational generation of new voices.

By Tracy K. Smith

Illustration: Ciara Phelan

Say It Loud

Poetry is language behaving fearlessly in pursuit of emotional truth. Sometimes this is a matter of saying plainly what is difficult to muster. Or it might involve being formally inventive in order to make space for feelings that seldom find their way into speech. In either case, poems invite readers to take part in such acts of courage, and lay claim to their spoils: a broader and more useful vocabulary for the joys and the sorrows of being human.

When I consider how the simple aim of poetry is being borne out by the current constellation of African American bards, I begin to believe we are in the midst of a creative flourishing to rival the Harlem Renaissance. I'm thinking of artists like Morgan Parker, whose There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé brings dark humor and pop-culture savvy to an examination of 21st-century female blackness. And Parker isn't alone. Black poets are engaged in the urgent enterprise of making sense of our present moment by writing boldly and resourcefully about the realities of race and gender in America. I notice most vividly a shared tendency to bear witness to what is starkest and most chastening—like police killings of unarmed black citizens—while also heeding what the incomparable Lucille Clifton rendered as a call, against tremendous odds, to joy:

come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed

Click through for six recent collections that deliver truth with originality and grace.

dying in the scarecrow's arms by Mitchell H. Douglas

Douglas's third collection opens with "Loosies," an elegy for Eric Garner in which a sense of violence and vulnerability touches everything after, from a landscape in winter, where "A cloud / of cardinals explodes / from a snow drift," to a visit by Jehovah's Witnesses, whose mission of deliverance the poem's speaker resists: "if we aren't talking / about bullets, I don't / want to ponder / salvation." Subtlest, perhaps, are Mitchell's nods to his own participation in gentrification, which is so often another kind of erasure of black life. One of the book's restorative gestures is a five-part love poem titled "Persist" that runs throughout the work, turning even the routine into a daily astonishment: "There is no sound / but our breath, the mirrors fogged, nothing / more to say."

In the Language of My Captor by Shane McCrae

In his immaculate latest, McCrae interweaves poems in the voice of Jim Limber, the adopted mixed-race son of Jefferson Davis, with a personal memoir of being adopted into the home of his white grandparents. In each case, the reader is led to ponder accounts of racism alongside nuanced and troubling instances of love. In two distinct sequences of persona poems, a black entertainer named Banjo Yes and an unnamed speaker who serves as a sideshow attraction see the world around them with a crystalline clarity that transcends their confines, transmitting a philosophy of race, fear, and privacy that calls the very terms of freedom and captivity into question: "I am / their honest mirror / I say Whether you're here / to see me or to see the monkeys / You're here to see yourselves."

Electric Arches by Eve L. Ewing

This remarkable debut begins with the clearest reminders of what African Americans have endured, then takes a running leap into rapturous possibility—not as mere escape, but rather as a way of summoning up the miraculous web of hope, knowledge, love, and belief that has sustained black life in this country through unforgiving centuries. While reading, I found myself continually thinking, I had no idea you could make poetry do that, followed by, Thank God she has done this. One of several standouts is "The Device," a long narrative poem about a work of technology built by black computer geeks, poets, and historians that crosses barriers of time and consciousness to tap into ancestral wisdom. But the briefer pieces here are just as revelatory, like these words from "True Stories about Koko Taylor": "Koko Taylor wrote songs with a blue ink pen. / Koko Taylor wrote rivers with a blue ink pen. / Koko Taylor wrote the Illinois Central Rail line with a blue ink pen. / Just got right on her knees and scratched it into the ground."

I'm So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On by Khadijah Queen

Queen's fifth book is a brilliant depiction of self-making and self-finding, a testament to our society's obsession with celebrity culture, and an unflinching acknowledgment of the joys and perils of seeking to be seen. This catalog of outfits, meticulously chosen and tenderly recalled, conjures portrait after portrait of a cognizance as it moves from youth through adulthood and into dawning middle age—one ready, finally, to say, "he also called me cutie I am 40 years old he called me girl & my patience for such thoughtlessness has fully waned." Amid America's unfolding conversation about sexual harassment, this is feminist critique that deftly and playfully pays tribute to the many real registers any woman inhabits from moment to moment. Queen's voice is a delight, and her vision of womanhood is at once a consolation and an admonition.

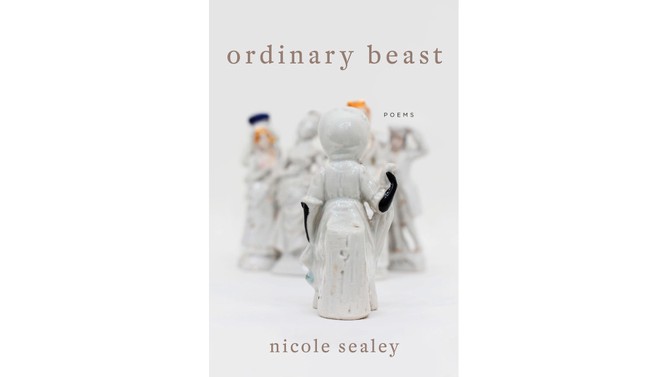

Ordinary Beast by Nicole Sealey

Quietly profound, Sealey's first collected work flows with an avid heart and mind through questions of love, inheritance, friendship, and family—things that sustain us from one day to the next, made more precious by their fragility. Such questions are universal, but they gain force at key junctures by the fact that Sealey's anchoring perspective is that of blackness. Her poem "hysterical strength" opens with a list of impossible feats of survival and swerves into a brief yet poignant treatise: "my thoughts turn to black people- / the hysterical strength we must / possess to survive our very existence, / which i fear many believe is, and / treat as, itself a freak occurrence." It is precisely her ability to think so nimbly, and map such lucid and inevitable-seeming paths from observation to credible theorem, that makes Sealey's words feel not merely beautiful, but useful in the way philosophy, or natural law, is useful.

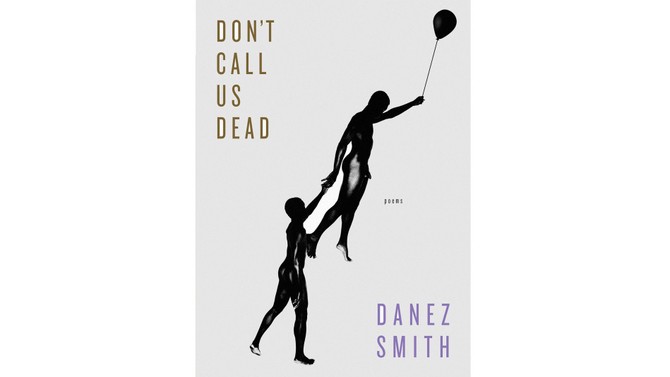

Don't Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Smith's searing second collection opens with "summer, somewhere," a 20-part suite imagining an afterlife where every slain black boy can finally live out his days in safety, cherishing a paradise "where everything / is sanctuary & nothing is a gun." It's part public lament, part defiant act of the imagination. Smith's capacity for compassionate invention is epic, as is the poet's courage for chronicling a harrowing personal relationship with HIV, that other threat claiming black men's lives with nearly the efficacy of bullets. Smith races across lexicons and spectra, pushing even the boundaries of typography in wrestling with the dreadful fact that the black male body is imperiled from both within and without, a declaration delivered with aphoristic chill in lines like: "some of us are killed / in pieces, some of us all at once."

Published 03/23/2018