Reading Questions for A Gate At the Stairs

Warning: May contain spoilers

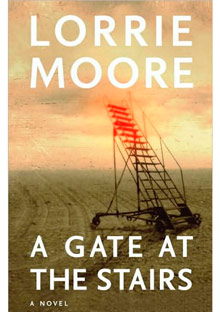

About this book: Tassie Keltjin has come from a small farming town to attend college in Troy, “the Athens of the Midwest.” She's swept into a thrilling world of books and films and riveting lectures, high-flying discussions about Bach, Balkanization, and bacterial warfare, and the witty repartee of her fellow students. At the end of the semester, Tassie takes a job as a part-time nanny for the newly adopted child of Sarah Brink, the owner of a trendy downtown restaurant, and her husband, Edward Thornwood, a scientist pursuing independent research. Tassie is enchanted by the little girl. Her feelings about Sarah and Edward are less easily defined, and as she becomes an integral part of their family, the mysteries of their lives and their relationship only deepen. She finds little to anchor her: a boyfriend turns out to be quite different from what he seems; vacations in her hometown are like visits to an alien country; and her loving, eccentric family no longer provides the certainties and continuity that shaped her childhood.

Lorrie Moore's ability to blend quick wit and hilarious observations of current trends with moving portraits of people struggling with loneliness, confusion, and the desire for love has made her one of the most admired writers of our time. Capturing the mood of post-9/11 America with astonishing deftness and precision, A Gate at the Stairs showcases Moore at the height of her powers.

— From the publisher

Read O 's review

Questions for Discussion

1. In addition to her sense of humor and intelligence, what are Tassie's strengths as a narrator? How does what she describes as “an unseemly collection of jostling former selves” (p. 63) affect the narrative and contribute to the appeal of her tale?

2. In the farming community where Tassie grew up, her father “seemed a vaguely contemptuous character. . . . His idiosyncrasies appeared to others to go beyond issues of social authenticity and got into questions of God and man and existence” (p. 19). Does the family, either intentionally or inadvertently, perpetuate their standing as outsiders? How does Moore use what ordinarily might be seen as clichés and stereotypes to create believable and sympathetic portraits of both the locals and the Keltjin family?

3. How does the initial meeting between Tassie and Sarah (pp. 10-24) create a real, if hesitant, connection between them? What aspects of their personalities come out in their conversation? To what extent are their impressions of each other influenced by their personal needs, both practical and psychological?

4. Are Sarah's ill-chosen comments at the meetings with Amber (p. 32) and Bonnie (pp. 89-90, p. 93) the result of the natural awkwardness between a birth mother and a potential adoptive mother or do they reveal deeper insecurities in Sarah? Does the adoption process inevitably involve a certain amount of willful deception, unenforceable promises (p. 87), and a “ceremony of approval . . . [that is] as with all charades. . . . wanly ebullient, necessary, and thin” (p. 95)?

5. What is the significance of Tassie's first impression of Edward-“one could see it was his habit to almost imperceptibly dominate and insult”-and her realization that “[d]espite everything, [Sarah] was in love with him” (p. 91)? Does Edward's behavior at dinner and the “small conspiracy” he and Tassie establish (pp. 112-114) offer a more sympathetic (or at least more understandable) view of him? Are there other passages in the novel that bring out the contradictions between his outward behavior and his private thoughts?