Where I Live

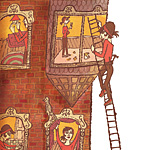

Credits: Illustration by Gilbert Ford

In the manual of life, there should be a chapter called "Stuff They Don't Tell You Beforehand." Sewing is more ironing and pinning than stitching, it would read; toilet-seat position will be the least of your marital worries; and oh, by the way, home ownership is really about home repair.

My three-story Victorian on the outskirts of Philadelphia is the first house I've owned, and when I bought it in 1996, I felt awash in fiscal wisdom and good fortune and artistic liberation. I had moved from Brooklyn to Philadelphia for many reasons, but mainly to reduce expenses so that I could write more of what I wanted, less of what would pay the rent. Before the ink on the mortgage papers had a chance to dry, however, I discovered that this house offered incontestable proof that the universe has a sense of humor.

All the details that drew me to the property in the first place hung to their functionality by a thread. The wood-sash storm windows fell apart if I thought about repainting them, the tiles of the master bath floor had come so loose I could vacuum them up, and that sunny little mudroom off the kitchen sucked in frigid winter air like a sponge. In my Pandora's Box, something fell apart every week and at every turn. The water line leaked when I tried to shut off its valve for winter, and the basement wall crumbled when I accidentally bumped into it with a laundry basket. One day, the dryer drum just refused to turn altogether. When visitors came to the 102-year-old home I called my own (or mine and the bank's), I was only half joking when I asked if they'd signed the waiver.

I spent the first year going through superintendent withdrawal. Having spent two decades as a renter, I'd see a leaking faucet or evidence of a mouse and fill with outrage, ready to kick up a fuss at...myself. I came to understand that charm is a synonym for things-that-will-eventually-break and they-don't-make-parts-for-that-anymore. "Fixing" was rarely cheap and never simple. First, I had to recognize that something was broken (harder than it sounds), then find someone who'd do the work (also surprisingly difficult), and learn enough about the issue (God bless diy.com) to understand what I was asking—and paying—for.

Inevitably, I'd face a Solomonic choice between a moderate short-term patch job and a pricey-but-long-term solution. I can't count how many times the contractor/plumber/painter would fix his face into a look of mock empathy and say, "Sure, you could go that route if money's all that's important to you." Each undertaking bore inherent philosophical quandaries: Can out-of-sight truly be out of mind when it comes to a collapsing chimney? How responsible am I, really, for other people's safety? If something is hardly ever used, is it really broken?

My three-story Victorian on the outskirts of Philadelphia is the first house I've owned, and when I bought it in 1996, I felt awash in fiscal wisdom and good fortune and artistic liberation. I had moved from Brooklyn to Philadelphia for many reasons, but mainly to reduce expenses so that I could write more of what I wanted, less of what would pay the rent. Before the ink on the mortgage papers had a chance to dry, however, I discovered that this house offered incontestable proof that the universe has a sense of humor.

All the details that drew me to the property in the first place hung to their functionality by a thread. The wood-sash storm windows fell apart if I thought about repainting them, the tiles of the master bath floor had come so loose I could vacuum them up, and that sunny little mudroom off the kitchen sucked in frigid winter air like a sponge. In my Pandora's Box, something fell apart every week and at every turn. The water line leaked when I tried to shut off its valve for winter, and the basement wall crumbled when I accidentally bumped into it with a laundry basket. One day, the dryer drum just refused to turn altogether. When visitors came to the 102-year-old home I called my own (or mine and the bank's), I was only half joking when I asked if they'd signed the waiver.

I spent the first year going through superintendent withdrawal. Having spent two decades as a renter, I'd see a leaking faucet or evidence of a mouse and fill with outrage, ready to kick up a fuss at...myself. I came to understand that charm is a synonym for things-that-will-eventually-break and they-don't-make-parts-for-that-anymore. "Fixing" was rarely cheap and never simple. First, I had to recognize that something was broken (harder than it sounds), then find someone who'd do the work (also surprisingly difficult), and learn enough about the issue (God bless diy.com) to understand what I was asking—and paying—for.

Inevitably, I'd face a Solomonic choice between a moderate short-term patch job and a pricey-but-long-term solution. I can't count how many times the contractor/plumber/painter would fix his face into a look of mock empathy and say, "Sure, you could go that route if money's all that's important to you." Each undertaking bore inherent philosophical quandaries: Can out-of-sight truly be out of mind when it comes to a collapsing chimney? How responsible am I, really, for other people's safety? If something is hardly ever used, is it really broken?