The Hungriness of the Human Heart

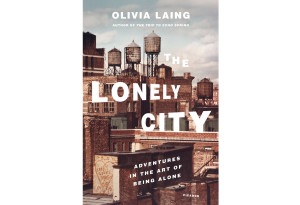

The author of the fascinating book The Lonely City talks about the loneliest birthday she ever had to face—and how she began to rethink her own isolation.

Photo: Luciano Lozano/ Getty Images

The loneliest period I ever spent was in New York, a few years back. A relationship had just ended, and though it hadn't lasted long, it crushed me more conclusively than any breakup I'd previously weathered.

In retrospect, I think the reason I found it so weirdly devastating was because I was still in the full flush of hope, radiant with the joy that I was finally being admitted to the charmed circle of coupledom. I was among the last of my friends to remain single and had begun to despair of ever getting married or having a family (though, in different moods, I regarded these things with deep ambivalence). To be presented with the possibility of permanent attachment, and then to have it swept away was almost unbearable. In the grim months that followed, I stopped sleeping or eating very much. My hair fell out and lay noticeably on the floor, adding to my disquiet.

My age didn't help. In my twenties, it was often me who did the leaving, certain that something better was just around the corner. But now, aged 34, I felt washed up and unconfident, paralyzed by my own longing for intimacy, my shameful inability to be sufficiently desirable. To make matters worse, I was living alone in a foreign country, drifting through a run of sublets. Hardly any wonder I tumbled into a deep, seemingly unbreakable spell of loneliness.

The worst day of that bleak period was my 35th birthday. Even now, years later, remembering it still makes me flinch. I was living in an apartment on the Lower East Side, in a building originally made to house garment workers. It was spring, and the city was awash with cherry blossoms. In the evenings, the sky would turn the color of a peach and I'd sit in my window with a drink, watching the people walking up Grand Street hand in hand. To this day, that's how loneliness feels to me: like watching couples laughing from behind a pane of glass.

I'm always uneasy about my birthday, but that year I was in a frenzy of anxiety. A friend and I decided we'd have a joint gathering, and I duly sent out emails and scoured online reviews to find the ideal bar for celebratory drinks. But as the day drew nearer, I sensed her enthusiasm cooling. Nothing had been confirmed and I felt too embarrassed to ask her what was happening, or to try and concoct an alternative plan. Then, on the eve of my birthday, she emailed, suggesting that we have a quiet dinner together, just the two of us. I was delighted. I'd spend the day alone, and in the evening we'd decide where to meet.

I woke to the sound of the fountain in the courtyard. I took myself for brunch, wandered around the West Village in the April sun, bought a book and a silky leopard-print bomber jacket, a talismanic garment: Be fierce, be wild, be self-sufficient! A game plan for the years to come. I walked home through a playground, where the boys were playing pick-up basketball beneath the plane trees. The loveliness of the city raised my spirits. I'd hit the hinge-point of my three score years and ten. Things could get better; anything could happen next.

But what happened next was silence. I waited and waited for an email or a text. I could have rung my friend, or called someone else and salvaged the evening, but I had become completely floored by misery, by the humiliation of being rejected, of being conclusively unwanted all over again.

It seems self-defeating, but in fact my inability to act was a classic instance of loneliness in action, a textbook example of how it accumulates and grows. Recent research by psychologists at the University of Chicago has shown that when people begin to feel lonely, the experience triggers significant changes in how their brains process social interactions. They become hyper-vigilant to what is known as social threat. In this state, which is entirely unconscious, they start to experience the world in negative terms, remembering instances of rejection over other friendlier interactions. As a result, they become increasingly risk-averse, growing daily more isolated, suspicious and withdrawn.

This is why loneliness tends to gets worse, and why people in its grips appear to give up and turn away from the world. Loneliness erodes our ability to reach out, to trust in others. The cycle of hyper-vigilant withdrawal explains why I couldn't say anything to my friend, or extend myself to make plans with anyone else. I couldn't risk any more rejection. I had to withdraw to protect myself, even though this meant I was cutting myself off from what I most desired: intimacy, closeness, company and love.

All this was made harder, of course, by the attendant issue of shame. Even if I could have reached out, I didn't want to tell anyone how I was feeling because we live in a culture that venerates attachment that holds both the family and the romantic pair as absolute ideals. People are afraid of loneliness; they withdraw from it, almost as if it could be contagious. Admitting it means risking that the people around you will back away, afraid of your contaminating, overwhelming need for company.

That's how I felt, lying on the blue couch in my borrowed apartment, waiting hopelessly for the phone to ring. But in the months that followed, I started to question this way of thinking, to pick apart its toxic logic. Once I knew that loneliness was distorting my thinking, I could work to counteract it. If I started feeling paranoid about a sharp remark from a friend or a delay in a response to an email—the sort of things that could send me into a tailspin of anxiety—I'd stop and remind myself that my ability to read situations was skewed towards paranoia. Slow down, I'd tell myself, with the deliberate gentleness you might use with a child.

I also began to question the shame that attaches to loneliness, especially once I realized how many people it affects. Current studies suggest that more than a quarter of American adults suffer from loneliness, independent of race, education and ethnicity. Marriage and high income serve as mild deterrents, but the truth is that few of us are absolutely immune to feeling a greater longing for connection than we find ourselves able to satisfy. Loneliness, I began to realize, is an inevitable consequence of our existence. We move in and out of relationships—not a single one of us is immune to loss.

As time went by, I started to realize that my loneliness was actually a powerful and fascinating state. It made me hyper-alert, acutely sensitive to the world outside me. If I could counteract the paranoia and the anxiety, then what I was really feeling was more a kind of openness, a longing that was exciting as well as scary. As the novelist Marilynne Robinson once said: "It's not a problem. It's a condition. It's a passion of a kind."

A passion: what a generous thing to say. When I think back now to those months in the Lower East Side, I think that I was in the grips of a passion, one that battered me and left me tender. Feeling lonely wasn't, as the psychologists claim, just a signal that I needed to date more, or to find someone to love. It was deeper and wilder than that. What I was experiencing in those months was an acute vulnerability. My initial response was to try and conceal it, to hide my longing and my desire for love, but as time wore on I realized that this state of openness and rawness had a beauty of its own.

Loneliness eventually taught me how to weather difficult emotions, to realize that they come and go, as impermanent as everything in this life. I'm still single, and I'm still lonely sometimes, but it doesn't scare me anymore.

Instead, it has made me become more compassionate to human vulnerability, the base state we all share, no matter how populated or rich our lives may seem. If you are lonely, there are other people feeling like you do—and one of them may be me. There's no need to feel shame. You're simply in touch with the hungriness of the human heart.

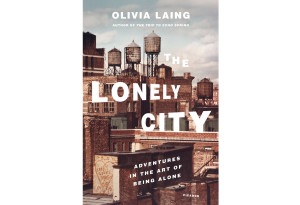

Olivia Laing is the author of The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone and To the River.

In retrospect, I think the reason I found it so weirdly devastating was because I was still in the full flush of hope, radiant with the joy that I was finally being admitted to the charmed circle of coupledom. I was among the last of my friends to remain single and had begun to despair of ever getting married or having a family (though, in different moods, I regarded these things with deep ambivalence). To be presented with the possibility of permanent attachment, and then to have it swept away was almost unbearable. In the grim months that followed, I stopped sleeping or eating very much. My hair fell out and lay noticeably on the floor, adding to my disquiet.

My age didn't help. In my twenties, it was often me who did the leaving, certain that something better was just around the corner. But now, aged 34, I felt washed up and unconfident, paralyzed by my own longing for intimacy, my shameful inability to be sufficiently desirable. To make matters worse, I was living alone in a foreign country, drifting through a run of sublets. Hardly any wonder I tumbled into a deep, seemingly unbreakable spell of loneliness.

The worst day of that bleak period was my 35th birthday. Even now, years later, remembering it still makes me flinch. I was living in an apartment on the Lower East Side, in a building originally made to house garment workers. It was spring, and the city was awash with cherry blossoms. In the evenings, the sky would turn the color of a peach and I'd sit in my window with a drink, watching the people walking up Grand Street hand in hand. To this day, that's how loneliness feels to me: like watching couples laughing from behind a pane of glass.

I'm always uneasy about my birthday, but that year I was in a frenzy of anxiety. A friend and I decided we'd have a joint gathering, and I duly sent out emails and scoured online reviews to find the ideal bar for celebratory drinks. But as the day drew nearer, I sensed her enthusiasm cooling. Nothing had been confirmed and I felt too embarrassed to ask her what was happening, or to try and concoct an alternative plan. Then, on the eve of my birthday, she emailed, suggesting that we have a quiet dinner together, just the two of us. I was delighted. I'd spend the day alone, and in the evening we'd decide where to meet.

I woke to the sound of the fountain in the courtyard. I took myself for brunch, wandered around the West Village in the April sun, bought a book and a silky leopard-print bomber jacket, a talismanic garment: Be fierce, be wild, be self-sufficient! A game plan for the years to come. I walked home through a playground, where the boys were playing pick-up basketball beneath the plane trees. The loveliness of the city raised my spirits. I'd hit the hinge-point of my three score years and ten. Things could get better; anything could happen next.

But what happened next was silence. I waited and waited for an email or a text. I could have rung my friend, or called someone else and salvaged the evening, but I had become completely floored by misery, by the humiliation of being rejected, of being conclusively unwanted all over again.

It seems self-defeating, but in fact my inability to act was a classic instance of loneliness in action, a textbook example of how it accumulates and grows. Recent research by psychologists at the University of Chicago has shown that when people begin to feel lonely, the experience triggers significant changes in how their brains process social interactions. They become hyper-vigilant to what is known as social threat. In this state, which is entirely unconscious, they start to experience the world in negative terms, remembering instances of rejection over other friendlier interactions. As a result, they become increasingly risk-averse, growing daily more isolated, suspicious and withdrawn.

This is why loneliness tends to gets worse, and why people in its grips appear to give up and turn away from the world. Loneliness erodes our ability to reach out, to trust in others. The cycle of hyper-vigilant withdrawal explains why I couldn't say anything to my friend, or extend myself to make plans with anyone else. I couldn't risk any more rejection. I had to withdraw to protect myself, even though this meant I was cutting myself off from what I most desired: intimacy, closeness, company and love.

All this was made harder, of course, by the attendant issue of shame. Even if I could have reached out, I didn't want to tell anyone how I was feeling because we live in a culture that venerates attachment that holds both the family and the romantic pair as absolute ideals. People are afraid of loneliness; they withdraw from it, almost as if it could be contagious. Admitting it means risking that the people around you will back away, afraid of your contaminating, overwhelming need for company.

That's how I felt, lying on the blue couch in my borrowed apartment, waiting hopelessly for the phone to ring. But in the months that followed, I started to question this way of thinking, to pick apart its toxic logic. Once I knew that loneliness was distorting my thinking, I could work to counteract it. If I started feeling paranoid about a sharp remark from a friend or a delay in a response to an email—the sort of things that could send me into a tailspin of anxiety—I'd stop and remind myself that my ability to read situations was skewed towards paranoia. Slow down, I'd tell myself, with the deliberate gentleness you might use with a child.

I also began to question the shame that attaches to loneliness, especially once I realized how many people it affects. Current studies suggest that more than a quarter of American adults suffer from loneliness, independent of race, education and ethnicity. Marriage and high income serve as mild deterrents, but the truth is that few of us are absolutely immune to feeling a greater longing for connection than we find ourselves able to satisfy. Loneliness, I began to realize, is an inevitable consequence of our existence. We move in and out of relationships—not a single one of us is immune to loss.

As time went by, I started to realize that my loneliness was actually a powerful and fascinating state. It made me hyper-alert, acutely sensitive to the world outside me. If I could counteract the paranoia and the anxiety, then what I was really feeling was more a kind of openness, a longing that was exciting as well as scary. As the novelist Marilynne Robinson once said: "It's not a problem. It's a condition. It's a passion of a kind."

A passion: what a generous thing to say. When I think back now to those months in the Lower East Side, I think that I was in the grips of a passion, one that battered me and left me tender. Feeling lonely wasn't, as the psychologists claim, just a signal that I needed to date more, or to find someone to love. It was deeper and wilder than that. What I was experiencing in those months was an acute vulnerability. My initial response was to try and conceal it, to hide my longing and my desire for love, but as time wore on I realized that this state of openness and rawness had a beauty of its own.

Loneliness eventually taught me how to weather difficult emotions, to realize that they come and go, as impermanent as everything in this life. I'm still single, and I'm still lonely sometimes, but it doesn't scare me anymore.

Instead, it has made me become more compassionate to human vulnerability, the base state we all share, no matter how populated or rich our lives may seem. If you are lonely, there are other people feeling like you do—and one of them may be me. There's no need to feel shame. You're simply in touch with the hungriness of the human heart.

Olivia Laing is the author of The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone and To the River.