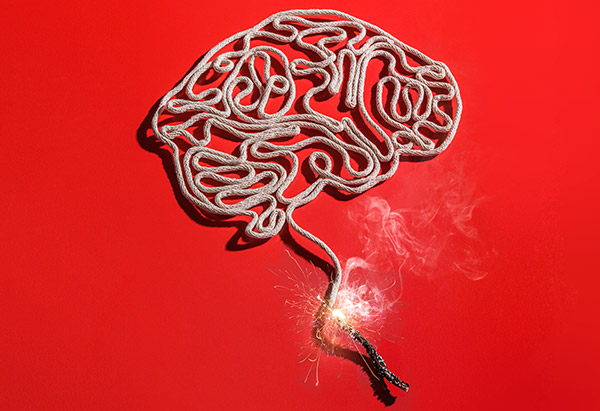

When a young journalist suddenly began exhibiting signs of violence and psychosis, no one suspected that her body had actually turned on her brain.

Illustration: Mauricio Alejo

In April 2009, Susannah Cahalan, a 24-year-old reporter for the New York Post, woke up strapped to a bed in a hospital room. She had no clear memory of the previous few weeks, though her medical records showed that she'd been psychotic and violent before lapsing into a profound catatonia. Her doctors had ordered a battery of blood tests and brain scans, but they revealed nothing. It took the brilliant neurologist Souhel Najjar, MD, to find the cause: Cahalan had a rare disease that caused her immune system to attack her brain. In her new book, Brain on Fire, Cahalan chronicles her terrifying ordeal and the desperate search for a cure. We asked her to walk us through her journey.

Q: Did you know you were sick before your hospital stay?

A: I knew something was wrong; I was constantly tired and I'd developed numbness on my left side. I'd also become paranoid that my boyfriend was cheating on me. I thought I was having a nervous breakdown. One psychiatrist told me I was bipolar. Then one day I walked through Times Square and the lights were painfully bright. I was experiencing photophobia, which preceded a massive seizure.

Q: When Dr. Najjar came in, he asked you to draw a clock face on a piece of paper. How did that help him diagnose your condition?

A: When I drew the clock, I squeezed all the numbers into the right half of the circle. My brain wasn't "seeing" the left half, which was a sign that the right hemisphere of my brain was inflamed. My doctors already suspected that I had an autoimmune disease, but the test enabled Dr. Najjar to finally connect all the symptoms—paranoia, psychosis, increased heart rate, and numbness on my left side—into a single diagnosis.

Next: What the test revealed about her brain

Q: Did you know you were sick before your hospital stay?

A: I knew something was wrong; I was constantly tired and I'd developed numbness on my left side. I'd also become paranoid that my boyfriend was cheating on me. I thought I was having a nervous breakdown. One psychiatrist told me I was bipolar. Then one day I walked through Times Square and the lights were painfully bright. I was experiencing photophobia, which preceded a massive seizure.

Q: When Dr. Najjar came in, he asked you to draw a clock face on a piece of paper. How did that help him diagnose your condition?

A: When I drew the clock, I squeezed all the numbers into the right half of the circle. My brain wasn't "seeing" the left half, which was a sign that the right hemisphere of my brain was inflamed. My doctors already suspected that I had an autoimmune disease, but the test enabled Dr. Najjar to finally connect all the symptoms—paranoia, psychosis, increased heart rate, and numbness on my left side—into a single diagnosis.

Next: What the test revealed about her brain

Q: He concluded that you had anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, a disease in which the immune system attacks proteins called NMDA receptors that lie on the surface of neurons. What do those receptors do?

A: NMDA receptors are concentrated in the areas that control learning and memory, higher functions like multitasking, and some of the more subtle aspects of personality. When the immune system makes antibodies that attack these receptors, people may have seizures and violent fits. They might act psychotic and paranoid, like I did, or become hypersexual and lewd. How you respond depends on the area of the brain that's most affected and the number of receptors damaged.

Q: After you were treated and the renegade antibodies were flushed from your system, your recovery took months. Did you ever worry that you might never fully recover?

A: Definitely. At first I could barely walk. I'm a fast talker, but my speech was really slow for almost a year. And I was lucky. I was only the 217th person in the world to be treated for the disease, but many people who get it never recover—and about 13 percent of adults who do recover eventually relapse. So now if I'm sitting in the subway and the lights seem brighter, I'll think, "Am I seeing things?" Or if I'm feeling moody, I'll worry, "Could I be losing my mind again?"

Q: As often happens with a rare illness, it took time to get the right diagnosis. Do you have any advice for people in a similar situation?

A: Get a second opinion. The first neurologist I saw just thought I was partying too much, and he stuck by that claim even after my family insisted that he was wrong.

More About Taking Care of Yourself

A: NMDA receptors are concentrated in the areas that control learning and memory, higher functions like multitasking, and some of the more subtle aspects of personality. When the immune system makes antibodies that attack these receptors, people may have seizures and violent fits. They might act psychotic and paranoid, like I did, or become hypersexual and lewd. How you respond depends on the area of the brain that's most affected and the number of receptors damaged.

Q: After you were treated and the renegade antibodies were flushed from your system, your recovery took months. Did you ever worry that you might never fully recover?

A: Definitely. At first I could barely walk. I'm a fast talker, but my speech was really slow for almost a year. And I was lucky. I was only the 217th person in the world to be treated for the disease, but many people who get it never recover—and about 13 percent of adults who do recover eventually relapse. So now if I'm sitting in the subway and the lights seem brighter, I'll think, "Am I seeing things?" Or if I'm feeling moody, I'll worry, "Could I be losing my mind again?"

Q: As often happens with a rare illness, it took time to get the right diagnosis. Do you have any advice for people in a similar situation?

A: Get a second opinion. The first neurologist I saw just thought I was partying too much, and he stuck by that claim even after my family insisted that he was wrong.

More About Taking Care of Yourself